Chapter 11 Chapter Nine: The Significance of This Period for World History

The early modern period from 1500 to 1763 is a relatively critical period in human history.It was during this period that the great discoveries revealed the existence of new continents and thus heralded the global phase of world history.It was also during this period that Europeans rose to the top of the world by virtue of their leadership in overseas activities.Some of the global interrelationships developed during these centuries have naturally grown stronger over time.In 1763 these interrelationships were much more important than they had been a century or two earlier, but they were extremely insignificant compared with their development in 1914.In other words, the years from 1500 to 1763 constitute a transitional period from the regional isolationism of the pre-1500 era to world power in nineteenth-century Europe.The purpose of this chapter is to analyze the exact nature and extent of the global relationships that developed in each jaw region.

The first and most visible result of Europe's overseas and onshore expansion was the unprecedented expansion of human horizons.Geographical knowledge is no longer confined to a region, continent or hemisphere.The shape of the entire Earth is determined and mapped for the first time.This work was mainly carried out by Western Europeans who took the lead in ocean-crossing expeditions.Europeans had only accurate knowledge of North Africa and the Middle East until the Portuguese began groping their way along the African coast in the early fifteenth century.Their knowledge of India is vague; their knowledge of Central Asia, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa is even more vague.The actual existence of North and South America and Australia was certainly not anticipated, let alone the existence of Antarctica.

By 1763, the situation was completely different.The major coastlines of most parts of the world, including the Atlantic coasts of North and South America, the Pacific coasts of South America, the coastlines throughout Africa, and the coasts of South and East Asia, are known in varying degrees of detail.In some areas, European knowledge extended beyond the coastline.Russians are fairly familiar with Siberia, Spaniards and Portuguese are fairly familiar with parts of Mexico, Central and South America.North of the Rio Grande, the Spaniards had explored much of the country in vain for gold and fabled cities, while the French and English, by canoe and the routes of the rivers and lakes known to the Indians, had traveled farther and farther. The area to the north roams widely.

The Pacific coast of North America, however, is largely unexplored; Australia, although its west coast was discovered by Dutch voyagers, is as a whole almost unknown.Likewise, the interior of sub-Saharan Africa remained largely blank; the same was true of Central Asia, where Marco Polo's accounts in the thirteenth century remained the main source of knowledge about Central Asia.In general, Europeans acquired knowledge of most of the world's coastlines during the period up to 1763.During the next period they will invade the interior of several continents and explore the Antarctic and Arctic regions.

The discovery of Europeans led not only to a new global perspective, but also to a new global distribution of races.In fact, before 1500, there was apartheid worldwide.Negroids are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and a few islands in the Pacific Ocean, Mongolians are concentrated in Central Asia, Siberia, East Asia, and North and South America, and Caucasians are concentrated in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and India.By 1763, the pattern had changed radically.In Asia, the Russians began to migrate slowly across the Ural Mountains into Siberia.In Africa, the Dutch had established a permanent colony at the Cape of Good Hope, where the climate was pleasant and the natives too primitive to mount effective resistance.By 1763, 111 years after the Dutch landed at Cape Town, they had advanced a considerable distance north and began to cross the Orange River.

The greatest changes in racial composition occurred in North and South America.Estimates of the Indian population before 1492 vary widely from 1 million to as high as 100 million.Whatever their number might have been, the catastrophic effects of the European invasion were universally acknowledged.The physical losses suffered during the conquest, the destruction of cultural patterns, the psychological trauma of the conquest, the burden of forced labor, the introduction of alcohol and new diseases—all these factors combined in various ways to decimate Indians everywhere.The overall Aboriginal population appears to have declined by 90% to 95% within a century.Hardest hit were the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean islands and tropical coastal areas, from which they disappeared entirely in about 30 years.Indigenous peoples in tropical highland regions such as Brazil and tropical lowland regions such as Paraguay are more resilient.Although they suffered very heavy losses, they were able to recover and constitute the race that gave rise to most of the contemporary American Indian population.Only in the twentieth century did the Indian populations in the American tropics approach their original numbers, and elsewhere they lag far behind.

The disappearing Indians were replaced by waves of immigration from Europe and Africa.The resulting settlements are of three types.A group consisting of Spanish and Portuguese colonies in which Iberian immigrants formed a permanently resident aristocracy that ruled over conquered Indians in the highlands and black slaves imported from Africa in the lowlands.Since there were far more men than women among European immigrants, they usually married Indian women or took them as mistresses.Thus came the mestizo population; and in many parts of North and South America they had begun to outnumber the Europeans and Indians.

A second settlement developed in the West Indies; there, too, Europeans—English, French, and Spaniards—formed a settled aristocracy, but ruled only by imported black labor.Initially, plantation owners hired indentured laborers from Europe to run their tobacco, indigo basket and cotton plantations.However, as they switched to sugar production in the mid-17th century, much more labor was needed, and slaves were brought in from Africa.For example, in British Barbados, there were only a few hundred blacks in 1640. However, by 1685, the number of blacks had reached 46,000, compared with 20,000 whites.same.In the French islands, by 1700 there were 44,000 blacks and 18,000 whites.

A third type of settlement in North and South America is found along the Atlantic coast.The native Indians in those places were either too few or too intractable to be an adequate source of labor, and, except in the southern colonies, the crops in that area were not a basis for the importation of black labor.In these cases, the English and French settlers cultivated the land themselves, worked as farmers, fishermen, or merchants, lived off their own labor, and developed societies composed entirely of Europeans.

In sum, mass migrations from Europe and Africa transformed North and South America from a purely Mongoloid continent into the most racially mixed region in the world.The migration of blacks continued until the mid-19th century, bringing the total number of slaves to about 10 million, while the number of European immigrants has been increasing steadily, reaching a very high figure by the beginning of the 20th century with nearly 1 million people arriving every year.The net result is that today America is inhabited by a majority of whites and a marked minority of blacks, Indians, Indian-whites, and mulattos (see Chapter 18, Section 1).

The new world racial order caused by the depopulation and migration of certain races has become so familiar that it is now taken for granted, and its enormous significance is therefore generally ignored.What happened in the period up to 1763 was that the Europeans claimed vast new areas for their possession; and in the following century they occupied these areas—not only North and South America, but And Siberia and Australia.The significance of this radical redrawing of the world's ethnic map can be estimated if one imagines that it was the Chinese, not the Europeans, who were the first to arrive and colonize the sparsely populated continent.Had that been the case, the Chinese today would probably be closer to three-quarters of the world's population than to one-quarter today.

The admixture of the human races was necessarily accompanied by a corresponding admixture of plants and animals.With a few insignificant exceptions, all plants and animals that are exploited today were domesticated by people in all parts of the world in prehistoric times.Their spread from their respective origins proceeded slowly until 1500; at this time, they began to be transplanted back and forth between continents by people across the globe.Captive animals of all kinds, especially horses, cattle, and sheep, are an important contribution from the Eastern Hemisphere.The American continent has comparable animals, where llamas and alpacas are of lesser value.Cereals of the Eastern Hemisphere were also important, especially wheat, rye, oats and barley.The Spaniards were lovers of orchards and brought to America a wide variety of fruit in addition to olive trees and European vines.In early Latin America, almost all missionary institutions and stately homes were surrounded by a walled orchard tending these European imports.

In return, American Indians contributed very rich food crops, notably corn and potatoes, but also cassava, tomatoes, avocados, sweet potatoes, peanuts, and several varieties of fava beans, squash, and winter squash.The cacao tree, another native plant of the Americas, was used by the Aztecs and Mayans to make the chocolate drink that their conquerors loved.These Indian plants are so important that today they account for at least one-third of all fertilizer produced in the world.

In addition to these food crops, American Indians cultivated two major cash crops: tobacco and cotton.Indians have long smoked tobacco in the forms we know today—pipes, cigars, corn husks, snuff.Tobacco spread rapidly from the American continent to the world, and in the process several new varieties were bred, of which the so-called Turkish tobacco of the eastern Mediterranean was; American continent.Varieties of cotton were known in the Eastern Hemisphere and the Americas before 1500, but most of today's commercial cotton is derived from varieties domesticated by the Indians.Also noteworthy are several Native American medicinal materials that feature prominently in modern pharmacology, notably coca leaves for cocaine and novocaine, curare for narcotics, and golden rooster for quinine. The bark of the bark, datura for analgesics, and cascara for laxatives.

Of course, the exchange of plants and animals was not limited to Eurasia and North and South America.The whole world was once involved in this exchange, as is evident in the case of Australia, which is now the world's leading exporter of primary products such as wool, mutton, beef and wheat, all of which originate from Alien species.The same is true of Indonesia, rich in rubber, coffee, tea and tobacco, and Hawaii, rich in sugar and pineapples.

By the latter part of the 18th century, for the first time in history, large-scale intercontinental trade had developed. By 1500, Arab and Italian merchants were already trafficking most of the luxury goods—spices, silks, gems, and essences—between one part of Eurasia and another.By the end of the eighteenth century, this limited trade in luxuries was transformed into a large-scale trade by the exchange of new, bulky necessities.This was especially the case with the Atlantic trade, as American plantations produced large quantities first of tobacco and sugar and later of coffee, cotton, and other commodities for supply to Europe.The plantations were monocultures, so they imported everything they needed, including grain, fish, cloth, and metal products.They also had to import labor, which led to a thriving triangular trade: European rum, cloth, guns, and other metal products were shipped to Africa, African slaves were shipped to America, and American sugar, tobacco, and gold and silver were shipped to Africa. Shipping to Europe.

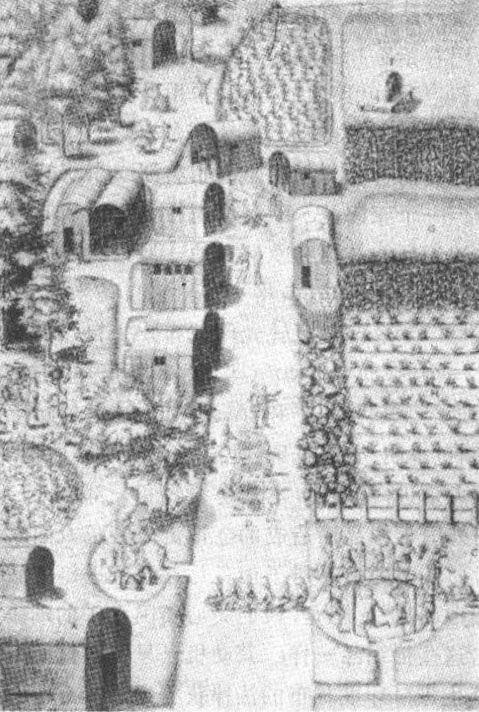

Late 16th Century Sekta (North Carolina) Indian Village

Another important aspect of the new, large-scale global trade of this era was between Western and Eastern Europe.Here again Western Europe received raw materials, especially corn for bread, which was in great demand due to the increase in population and the conversion of large arable lands to pastures.At Danzig, the main port of the Baltic grain trade, the prices of rye, barley, and oats rose by 247%, 187%, and 185%, respectively, between 1550 and 1600.This situation led to a huge increase in the export of grain and other raw materials, so that the prices of Polish and Hungarian exports to the West during these decades were usually twice the price of imports.Poland, Hungary, Russia, and finally the Balkan states received textiles, arms, metal products, and colonial goods; in return they provided grain, cattle, hides, ship's supplies, and flax.They also provided furs; furs were obtained by the Russians in Siberia (see Chapter VIII, Section 4) by exploiting native labor in the same way that the Spaniards obtained gold and silver in America.

Europe trades less with Asia than with North and South America or Eastern Europe for two main reasons.One reason is that the European textile industry opposes the import of cotton fabrics from Asian countries.The names of these cotton items in English and some other European languages reflect their origin. "Gingham" (striped flat cloth) comes from the Malay word meaning "striped", "chintZ" (rubbed calendered cloth) comes from the Hindustan word meaning "spotted" and " Calico" (printed flat cloth) and "muslin" (fine flat cloth) are derived from the place names "Calicut" and "Mosul" respectively.These foreign cotton fabrics are very popular in Europe because of their light weight, bright colors, low price and especially washability.They began to be imported in large quantities, and there was objection from the local textile circles and from those who feared that the loss of gold and silver to pay for foreign cottons would endanger the security of the country.Some English pamphleteers slandered these imports as "bad goods for frivolous women."But their concern for the modesty and character of English women is as obvious as their motive for attacking these cottons.European organizing circles put enough pressure on their respective governments to secure the passage of laws prohibiting the importation of Indian cotton cloth.These laws were not universally followed, however, they did have the effect of significantly reducing the volume of trade with Asia.

Another reason for restricting trade between Europe and Asia was the difficulty of finding items to sell in Asian markets.This problem has been around since classical times; when the Roman Empire ran out of gold to pay for Chinese silk and Indian textiles. The same was true in the 16th, 17th, and 19th centuries, when Asia remained uninterested in European goods, and Europe grudgingly paid for the Asian products it wanted in gold and silver.Western businessmen are often exhausted as they try to find a way out of the impasse.The Amsterdam company had exported to Thailand "thousands of Dutch engravings to be sold in the market in Patani. Among them were the Madonna (on instructions from Calvinist merchants to prevent sale to Buddhists and Muslims) and depictions of the Bible works of middle plot; there are Livy's historical stories, engravings suitable for the Siamese who valued the classics, and finally, there are pictures that appeal to people more generally, that is, a group of nudes and less decorous. illustration.” In fact, Europe did not solve this problem in trade with Asia until the development of power machinery in the late eighteenth century. At the end of the eighteenth century, the situation changed completely, as Europe flooded Asia with cheap machine-woven textiles.Until then, however, East-West commerce had been hampered by Asia's willingness to accept European gold and silver, and little else.This situation explains the following rather revealing statement by Voltaire in the second half of the eighteenth century:

What is the significance of this new world economic relationship?First, the first international division of labor has been completed on a large scale.The world is becoming one economic unit.North and South America and Eastern Europe (along with Siberia) produced the raw materials, Africa supplied the manpower, Asia supplied the luxuries of all kinds, while Western Europe directed these global activities and increasingly devoted itself to industrial production.

The new global economy raises labor supply issues in raw material production areas.American plantations solved this problem by importing African slaves on a large scale (see Table 1).Negroes are now in exactly the same areas that once specialized in plantation agriculture—northern Brazil.The West Indies and the American South—there are a lot of them.This leaves a painful legacy, as these areas are still ravaged today by fundamental problems that began in colonial times — race and underdevelopment.The current racial struggles in the American ghettos and Caribbean islands are the end result of more than four centuries of transoceanic slave trade, while the underdevelopment of Latin America as a whole is nothing more than Spanish and Portuguese colonies (compared with Spain and Portugal). itself) to the continuation of the economic dependence of Northwest Europe.

The price paid by North and South America for participation in this new global economy was slavery, and the price paid by Eastern Europe was serfdom.The basic reason was the same - the need for an abundant and reliable supply of cheap labor to produce goods for the lucrative Western European market.Prior to this time, the Polish and Hungarian nobles demanded a minimum of labor from the peasants—3 to 6 days of compulsory labor a year—because there was no incentive to increase production.But when market-oriented production became profitable, the aristocracy quickly responded by dramatically increasing the hours of compulsory labor to one day a week, and by the end of the sixteenth century to six days a week.In order to ensure that the peasants continued to undertake the forced labor, laws restricting the free movement of the peasants were gradually passed.In the end, the peasants were completely tied to the land, and thus became serfs without freedom of movement, and were extorted by the nobles.

A similar process of development existed in the countries of the Balkans under Turkish rule.There, all the warriors (knights) who made meritorious service during the conquest period were enfeoffed, and since then Timar was the town.This timar system allowed peasants to use their small plots of land for generations in return for their small taxes and servitude, while knights, if they failed to fulfill their military obligations, could be deprived of their timar. In the 16th century this extraordinarily benevolent institution was undermined by the weakening of imperial authorities and the attractiveness of Western markets.The knights converted their timars into private estates that Chiflik could inherit; farmers on the estates were forced to accept tenancy terms or be evicted from the land.After paying the taxes levied by the state and the part of the harvest required by the knights, the tenants usually left only about one-third of their produce.Although they were not legally bound to the land in the way Polish, Hungarian, and Russian serfs were, in practice they were just as effectively anchored to the land by debts to knights.It is no accident that this Chiflik system spread in fertile plains such as Thessaly, Macedonia, the Maritsa and Doben river valleys, where large-scale production for Western markets was possible.It is no accident, moreover, that peasant revolts coincided with the spread of the Chiflik system; just as slave revolts were the result of plantation slavery in America, so peasant revolts were the result of serfdom in Eastern Europe.

Table 1 Approximate number of slaves imported to North and South America

The new global economy is also having an extremely important impact on Africa, both negatively and positively.It is estimated that between 35 million and 40 million Africans were trafficked to North and South America, and the slave trade is the main cause of this loss; however, this figure needs to be confirmed by sufficient investigation.In reality, only about 10 million slaves made it to their destination.The others all died en route in Africa or at sea.The impact of the slave trade varied from region to region.Angola and East Africa have suffered greatly because the population there is relatively small to begin with and often economically close to subsistence, so even small losses can be devastating.In contrast, West Africa was more economically advanced and thus more densely populated, so the raids of slave traders were less destructive.From the perspective of the whole continent, since the period of slave removal lasted from 1450 to 1870, and the total population of sub-Saharan Africa whose slaves were removed is estimated to be 70 million to 80 million, the impact on population is relatively tiny.The slave trade, however, had a corrosive and disruptive effect on Africa's entire coastal region from Senegal to Angola and the interior for four or five hundred miles.The arrival of European slave traders, carrying goods such as rum, guns, and metal utensils, set off a chain reaction: Invasions of the interior were hunted for slaves, and various groups fought for control of this profitable and militarily decisive trade with each other.The overall impact of the slave trade must have been devastating as some groups and regions such as the Ashanti Federation and the Kingdom of Dahomey rose to dominance and others such as the Yoruba, Benin Civilization and the Kingdom of Congo declined .

However, the slave trade did include trade in addition to the possession of slaves.In return for selling their own countrymen to the Europeans, the Africans received not only alcohol and firearms but also certain utilitarian and economically productive goods, including textiles, tools, and supplies for local blacksmith shops and workshops. Raw materials used.A more important positive effect in the long run was the introduction of new food crops from North and South America.Corn, cassava, sweet potato, pepper, pineapple, and tobacco were introduced to Africa by the Portuguese and spread very quickly among the tribes.These new foods could actually feed large numbers of people, perhaps more than were lost in the slave trade.

Of the continents, Asia was the least affected because it had become militarily, politically, and economically strong enough to avoid direct or indirect conquest.Much of Asia was completely oblivious to the stubborn, obnoxious European traders who were appearing along the coast.Only a few coastal areas of India and certain islands of the East Indies felt the effects of European economic expansion to a large extent.The attitude of Asia as a whole was best expressed by the Chinese Emperor Qianlong in his reply to a 1793 letter from King George III of England requesting diplomatic and trade relations, saying: "In governing this vast world , I have only one object in mind, which is to maintain a perfect government and to perform the duties of the state: exotic, expensive things do not interest me. ... As your ambassador can see with his own eyes, we have everything. I Strange or delicate objects are not valued at all, and therefore, the products of your country are not needed."

Europe was also affected by the new global economy, but the effects were all positive.Europeans were the earliest middlemen in world trade.They opened up new ocean routes and provided the necessary capital, ships, and expertise.Of course, they would have benefited most from the slave trade, sugar cane and tobacco plantations, and trade with the East.Some of the benefits accrued slowly to the masses of the European people, as the case of tea shows; when tea was introduced to England around 1650, it was worth about £10 a pound, but a century later it had become common consumption.Even more important than the effect on living standards was the stimulating effect of the new global trade on the European economy.As will be mentioned later, the Industrial Revolution which began in the late eighteenth century owes much to the accumulation of capital from overseas undertakings and the growing demand for European manufactures in overseas markets.

Therefore, it was during this period that Europe advanced by leaps and bounds and quickly rose to the top of the world economy.The overall result is positive, as the world division of labor leads to an increase in world productivity. The world in 1763 was richer than it was in 1500, and economic growth has continued to the present.But from the very beginning, Northwest Europe, as the world's entrepreneur, reaped most of the benefits at the expense of other regions.What this damage entailed is clear from the current racial struggles, the stark differences between rich and poor countries, and the still perceptible scars of serfdom across Eastern Europe.

During the period up to 1763, global political relations, as well as economic ones, underwent fundamental changes.Western Europeans were no longer surrounded by the expanding Islam at the western end of Eurasia.Instead, they have surrounded the Muslim world from the south by winning control of the Indian Ocean, while the Russians have surrounded the Moslem world from the north by conquering Siberia.At that time, Western Europeans also discovered the Americas, opening up large areas for economic development and colonization.In doing so, they amassed enormous resources and power; these resources and power further strengthened their vis-à-vis Islam and proved increasingly decisive in the next century.

All this points to a fundamental and significant change in the balance of power in the world—a change comparable to the previous change in the balance of population.In the past, the Muslim world had been the center of an initiative that probed and pushed in all directions—into Southeastern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia.Now a new center has arisen capable of functioning on a global scale, not just on the Eurasian scale.From this new center, first from the Iberian Peninsula and then from the northwest, routes of trade and political influence stretched in all directions around the world—west to North and South America, south around Africa, east to India and bypass Southeast Asia.

This does not mean that Europeans actually controlled all of these areas by 1763.It did mean, however, that Europeans effectively dominated sparsely populated areas—North and South America, Siberia, and later Australia—although their actual occupation on a continental scale did not begin until the nineteenth century.In Africa and Asia, however, apart from the Dutch invasion of the Cape of Good Hope and the East Indies, the Western Europeans acquired only a few coastal strongholds during this period.Elsewhere, the indigenous peoples were too powerful and highly organized to allow a repetition of what happened in North and South America and Siberia.

In West Africa, for example, coastal chiefs carefully guarded their vantage point as intermediaries between interior tribes and Europeans; European invasions of the interior were deterred by their opposition and climatic difficulties.Europeans, therefore, were content to set up coastal trading posts through which they traded slaves and any other commodity that might yield a profit.

In India, Europeans remained alienated for 250 years after da Gama arrived in 1498.During these two and a half centuries, they were able to trade in a few ports, but this was apparently only possible with the grudging consent of the native rulers.For example, in 1712 John Rosso, Commander of Fort William and grandson of Oliver Cromwell, began a petition to the Mughal emperor with the following address: "John Russell kowtowed and made the smallest grain of sand request with the respect due to a slave..." It wasn't until the end of the eighteenth century that the British were strong enough to take advantage of the disintegration of the Mughal Empire and begin their conquest of Indian territory.

In China and Japan, the possibility of European invasion of territory, as the Russians discovered when they entered the Amur Valley, was non-existent.Even trade with the Far East was unstable, governed by arbitrary laws that could not be challenged. In 1763, more than two centuries after the Portuguese arrived in the Far East, Western merchants could only do business in Canton and Nagasaki.Even the Ottoman Empire had lost only its outlying territories across the Danube, though it was dying and vulnerable to the land and sea powers of Europe.

We can conclude that, in the political sphere as in the economic sphere, Europe in 1763 was halfway.It was no longer a relatively isolated, unimportant peninsula of Eurasia.It has expanded overseas and on land, establishing control over deserted and militarily weak North and South America and Siberia.But in Africa, the Middle East, and South and East Asia, Europeans had to wait until the nineteenth century to claim their domination.To underscore the transitional nature of these centuries, it should be emphasized that while the Western Europeans were carrying out their global campaign of outflanking by sea, the Muslims still had sufficient impetus to continue their advance by land into Central Europe, besieging Vienna in Central Europe in 1683 , and invaded sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, winning new converts there.

The imposition of European culture, as well as the imposition of European political domination, depended on the conditions of the respective indigenous societies.The English and the French, for example, were able to transfer their respective cultures to North and South America in their entirety because the native peoples had either been wiped out or had been driven out.Even in this case, however, the Indians still had a clear influence on the civilization of the whites north of the Rio Grande.In the early days of contact between the English and French immigrants and the Indians, the Indians felt comfortable with their own social norms and believed that their culture was at least comparable to that of the invading whites. This is shown by the reaction of the Iroquois when it was proposed at a meeting in 1744 that the Iroquois send some of their children to Williamsburg for a European-style education.They objected with the following proposal: "If the English lords send twelve or twenty-four of their children to Onondaga, the Union Parliament will take care of their education, and bring them up in the true best way to bring them up. This unwavering independence of the Indians prompted Benjamin Franklin to write in 1784: "We call them savages because their way of life is different from ours, and we consider ours to be the perfect culture: they Do the same with their way of life." True, whites had the numbers, organization, and power to pillage Indians and take over entire continents.But in the end, white people found that they had unknowingly adopted many features of local Indian culture in their vocabulary, literature, clothing, medicines, and the crops they grew and consumed.

Western ships arriving in Tianjin

The influence of the Indians on the Latin American civilization that developed south of the Rio Grande was also great.Unfortunately, this influence has not been fully investigated so far, because most research has focused on the opposite process, the influence of Iberian culture on Indians.Yet even the casual traveler to Latin America cannot fail to notice signs of Indian cultural remnants.For example, adobe bricks are used to build houses, and pine logs that have not been sawn are used to make the rafters.Likewise, the rug that is draped over the shoulders, the Serapu, has Indian tribe origins, as does the poncho, made of two rugs sewn together with a central open collar.Roman Catholicism, prevalent in much of Latin America, is a mixture of Christian teachings and practices and Indian beliefs and customs.Although the Indians had given up the names of the local gods, they assigned the attributes of these gods to the Virgin Mary and saints, expecting these idols in the Catholic pantheon to be like their gods, healing diseases, controlling the weather and Keep them safe from harm - their gods, they believe, have done so in the past.Perhaps the clearest signs of Indian influence can be found in Latin American cuisine.Corn dumplings, corn tortillas and all kinds of spicy dishes are based on the two famous Indian broad beans and corn.

In the period before 1763, apart from the spread of the new and most important food crops already mentioned, the influence of Europeans on the indigenous cultures of Africa and Eurasia was insignificant.In West Africa, indigenous chiefs largely confined European traders to their coastal trading posts.The attitude of these chiefs is strikingly revealed in the following statement by a chief of the Gold Coast, Kwami Ansa, on January 20, 1482.These remarks were in reply to a high-ranking Portuguese dignitary.He arrived there with a formidable retinue, and asked permission to build a fort there.

In the ancient centers of civilization in the Middle East, India, and China, the native peoples were, as one might expect, completely unimpressed with the culture of the European invaders.The Muslim Turks, though most closely related to Christian Europeans, looked down upon them extremely.Even in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the Turks themselves were in decline, they did not hesitate to express contempt for Christian pagans. In 1666, the Turkish prime minister suddenly yelled at the French ambassador: "Don't I know that you, you are a heretic, a godless person, a pig, a dog, a dung eater?"

对欧洲和欧洲人的这种傲慢不恭的态度,在很大程度上可用基督教和伊斯兰教之间由来已久的不和来解释。欧亚大陆其他地方对欧洲人的反应不是那么傲慢无礼,但同时也没有尊敬的表示,更不用说敬畏了。当葡萄牙人到达锡兰时,科伦坡的土著官员将以下这份对新来的人的颇为客观的评价送交在康提的国王:“在我们的科伦坡港口,来了一些皮肤白皙但长相颇不难看的人;他们戴铁帽、穿铁农;他们不在一个地方停留片刻列也们老是到处走来走去;他们吃大块的石头'硬饼干',喝血'碰巧,地道的马德拉葡萄酒';他们用两、三块黄金或白银买一条鱼或一只酸橙。……”这位科伦坡官员是个目光敏锐的人,接着又说,“他们的枪炮非常好。” 后面一句评语特别予人以启示:凡是在欧洲人给别的人们留下印象的地方,必定是由于其技术成就的缘故。

在印度大陆,当已在果阿安身的葡萄牙人于1560 年引进宗教法庭时,诸土著民族的反应是非常消极的。从]6O0至1773年,因有异教观点而被处火刑的受害者有73名。印度居民不能不注意到天主教的一种不一致性:它监禁、折磨和以火刑烧死那些其唯一罪行是持异端观点的人,而同时,又阻止那些将自焚视作一种崇高美德的寡妇自愿让火烧死。此外,欧洲冒险家在印度的不法和狂暴行为进一步降低了印度人民对天主教徒的评价。1616年,有人对英国牧师特里先生说:“基督教是魔鬼的宗教;基督教徒时常酗酒;基督教徒时常干坏事;基督教徒时常打人;基督教徒时常辱骂别人。”

由于耶稣会传教士的卓越才能和学问上的造诣,中国人对欧洲人的反应开始时比较良好(如第四章第四节所提到的)。耶稣会会土成功地赢得了一些皈依者,包括少数学者和一些皇室成员。然而,即使是具备天文学、数学和地理学知识的能干的耶稣会会土,也没有给中国人留下过深的印象。有位作者因为基督教接近于儒教,并惊奇地发现有些欧洲人是“真正的绅士”,所以赞扬欧洲人,写了一篇最表示赞赏的评论:

这篇颂辞是个例外。中国大部分学者都拒绝西方科学和西方宗教。在教皇克雷芒十一世于1715 年3月颁布“自该日”训令、禁止基督教徒参加祭祖或尊孔的仪式之后,中国皇帝康熙轻蔑地说:“读了这篇训令,我所能说的是,西方人,象他们那样愚蠢的人,怎么能反对中国的伟大学说呢?他们当中没有人能透彻地理解中国的经籍;当他们说话时,其中大部分人是可笑的。我现已阅完的这篇训令颇类似于佛教徒和道教徒的种种迷信玩意儿,但是,没有任何东西象这篇训令那样充满了大错。”就当时中国民众对欧洲人的看法而论,它或许准确地反映在以下这句格言中:只有他们中国人拥有双眼,欧洲人是独眼,世界上所有其他的居民均为瞎子。假如是这种气氛,那么可以理解:1763年以前,除诸如夭文学之类的某些专门的知识领域外,欧洲人对中国文明的影响是微不足道的。

虽然这一时期中,中国人、印度人和土耳其人对欧洲人的文化没有印象,但欧洲人却相反,对他们在君士坦丁堡、德里和北京所看到的东西印象非常深。他们首先熟悉奥斯曼帝国,他们的反应是尊敬、钦佩和不安。迟至1634 年即帝国开始衰落后,一位富有思想的英国旅行者还下结论说,土耳其人是“近代唯一起伟大作用的民族”,“如果有谁见到过他们最得意的这些时代,他就不可能找到一个出土耳其更好的地方。”在较早的年代里,在苏里曼一世统治期间,哈普斯堡皇室驻君士坦丁堡的大使、富有见识且观察力敏锐的奥吉尔·吉斯莱恩·德· 巴斯贝克也表示过类似的赞美。1555年,巴斯贝克在给朋友的一封信中,把苏里曼比作雷电——“他猛击、毁坏和消灭一切挡道的东西。”巴斯贝克不仅对奥斯曼帝国的力量,而且对基于严格的人才制度的奥斯曼官僚机构的效率也印象很深。

17 世纪期间,奥斯曼帝国失去了在欧洲人中间的声誉。许多衰败的征兆日益明显起来,其中包括王朝的堕落、行政管理的腐败和军事上的软弱。但当时,欧洲知识分子正被有关传说中的遥远的中国文明的许多详细的报道所强烈地吸引住。这些报道以耶稣会传教士的报告为根据,引起了对中国和中国事物的巨大热情。实际上,17 世纪和18世纪初叶,中国对欧洲的影响比欧洲对中国的影响大得多。西方人得知中国的历史、艺术、哲学和政治后,完全入迷了。中国由于其孔子的伦理体系、为政府部门选拔人才的科举制度、对学问而不是对作战本领的尊重以及精美的手工艺品如瓷器、丝绸和漆器等,开始被推举为模范文明。例如,伏尔泰(1694-1778年)用一幅孔子的画像装饰其书斋的墙,而德国哲学家莱布尼茨(1646—1716年)则称赞中国的康熙皇帝是“如此伟大、人间几乎不可能有的君主,因为他是个神一般的凡人,点一下头,就能治理一切;不过,他是通过受教育获得美德和智慧……,从而赢得统治权。”

18 世纪末叶,欧洲人对中国的钦佩开始消逝,一方面是由于天主教传教士正在受到迫害,一方面是由于欧洲人开始对中国的自然资源比对中国的文化更感兴趣。这种态度的转变反映对1776至1814年间在巴黎出版的16卷《关于中国人的历史、科学和技术等等的学会论文集》中。该书第十一卷于1786年问世,里面几乎仅收录关于可能会使商人感兴趣的资源——硼砂、褐煤、水银、氨草胶、马、竹以及产棉状毛的动物——的报告。

正如欧洲人的兴趣在17 世纪从奥斯曼帝国转移到中国一样,到了18世纪后期,欧洲人的兴趣又转移到希腊,并在较小程度上转移到印度。古典希腊人成为受过教育的欧洲人极其喜爱的人。1778年,一位德国学者写道,“我们怎么能相信,在欧洲的导师希腊人会阅读以前,东方诸野蛮民族已产生编年史和诗歌,并拥有完整的宗教和伦理呢?” 不过,欧洲有少数知识分子确开始热中于印度文化。欧洲一般公众在这时以前很久就已知道印度,而且,有关德里“莫卧儿大帝”的财富和豪华生活的报道已使他们为之激动。1658至1667年间在德里侍候皇室的法国医生弗朗索斯·伯尼埃,曾对著名的孔雀宝座作了以下描述;我们可以想象出当时的人们对这段描述的反应。

随着欧洲人逐渐注意到印度人的古代文学,他们对印度及其文明的肤浅认识开始深化。印度博学家不愿意把自己的神圣的学问传授给外国人。但是,少数欧洲人,多半为耶稣会神父,获得了梵语、文学和哲学方面的知识。德国哲学家叔本华(1788—1860年)就象莱布尼茨被中国人迷住那样,着迷于印度哲学。1786年,英国学者威廉·琼斯爵士向孟加拉亚洲学会宣布,“无论梵语多么古旧,它具有奇妙的结构;它比希腊语更完美,比拉丁语更词汇丰富,比希腊语和拉丁语中的任何一者更优美得多。”

从1500 至1763年的近代初期,是前几个时代中的地区孤立主义与19世纪的欧洲世界霸权之间的一个中间阶段。在经济上,这一时期中,欧洲人将他们的贸易活动实际上扩展到世界各地,不过,他们还不能开发那些巨大的本陆块的内地。虽然洲际贸易达到了前所未有的规模,但贸易量仍远远低于以后世纪中所达到的数量。

在政治上,世界仍完全不是一个单一的整体。震撼欧洲的有名的六年战争未曾影响到密西西比河以西的南北美洲、非洲内地、中东大部分地区和整个东亚。虽然欧洲人已牢固地控制了西伯利亚、南美洲和北美洲东部地区,但到当时为止,他们在非洲、印度和东印度群岛仅拥有少数飞地,而在远东,只能作为商人从事冒险活动,而且,即使以商人身份活动,他们还必须服从最具有限制性、最任意的规章制度。

在文化上,这是一个眼界不断开阔的时期。整个地球上,一些民族正注意到其他民族和其他文化。总的讲,欧亚大陆诸古代文明给欧洲人的印象和影响较后者给前者的印象和影响更深。当欧洲人发现新的海洋、大陆和文明时,他们有一种睁大眼睛的惊讶感觉。他们在贪婪地互相争夺掠夺物和贸易的同时,还表现出某种谦卑。他们有时甚至经历了令人不安的良心的反省,如在对待西届美洲的印第安人时所显示的那样。但是,在这一时期逝去以前,欧洲对世界其余地区的态度起了显著变化。欧洲的态度变得愈来愈粗暴、冷酷和偏狭。19世纪中叶,法国汉学家纪尧姆·波蒂厄抱怨说,在莱布尼茨的时代曾强烈地使欧洲知识分子感兴趣的中国文明,“如今几乎没有引起少数杰出人物的注意。……这些人,我们平日视作野蛮人,不过,在我们的祖先居住于高卢和德意志的森林地带的数世纪以前,已达到很高的文化水平,如今,他们却仅仅使我们产生极大的轻蔑。”本书第三篇将论述欧洲人为何开始感到自己胜过这些“劣种”,以及欧洲人如何能将自己的统治强加于他们。

公元1500 年之后的时代是具有重大意义的时代,因为它标志着地区自治和全球统一之间冲突的开端。在这以前,不存在任何冲突,因为根本就没有全球的联系,遑论全球统一。数万年以来,人类一直生活在地区隔绝的状态中。当最初的人类大概从非洲这个祖先发祥地散居开来时,他们就失去了与其原先邻居的联系。当他们向四面八方扩散开来,直到占据了除南极洲以外的所有大陆时,他们持续不断地重复了这一过程。For example.最初的蒙古种人穿越西伯利亚东北部到达阿拉斯加后,他们又向整个北美和南美地区继续推进。他们在彼此相对隔绝的新的社会中定居下来。几千年来,他们各自形成了独特的方言和文化,甚至在形体特征上也产生了差别。这一过程扩展到全球,因而一直到公元1500年,种族隔离现象遍存于全球。所有的黑人或黑色种人都生活于非洲,所有的白人或高加索种人都生活于欧洲和中东,所有的蒙古种人都生活于东亚和美洲,而澳大利亚土著居民则生活于澳洲。

公元1500 年前后,当西方进行海外扩张时,这种传统的地区自治便开始让位于全球统一。各个种族不再互相隔绝,因为成千上万的人自愿或不自愿地移居到新的大陆。由于欧洲人在这一全球历史运动中处于领先地位,所以正是他们支配了这个刚刚联成一体的世界。到19世纪,他们以其强大的帝国和股份公司在政治上和经济上控制了全球。他们还取得了文化上的支配地位,于是西方文化成了全球的典范。西方文化被等同于文明,而非西方文化天生就下贱。这种西方的霸权在19世纪时不仅欧洲人而且非欧洲人都认为是理所当然。在人们看来,西方的优势地位几乎是天经地义,是由上帝安排的。

如今20 世纪,钟摆开始再次摆向地区自治。欧洲用了四个世纪(1500-1900年)才建立起世界范围的统治。而时间仅过去40年,欧洲这种统治就土崩瓦解了,这一瓦解过程开始于第一次世界大战之后。而到第二次世界大战结束后又加快了步伐。政治瓦解表现为帝国统治的终结。经济崩溃与共产主义社会的兴起同时,即开始于1917年苏俄的建立,并因第二次世界大战后共产主义扩展到中国、东南亚、非洲和古巴而不断加速。文化分化范围更为宽广,西方文化不再被认为与文明同义,而非西方的文化也不再等同于野蛮。

目前,西方文化在全世界不仅直接受到挑战。甚至被抵制。1979 年11月,美国使馆人员在德黑兰被扣留为人质时,西方记者曾书面向那些年轻的捕手提出许多问题。后者集体作出回答,他们的答复如下:“西方文化对殖民主义者来说是一种极好的手段,一种使人疏远本民族的工具。通过使一个民族接受西方和美国的价值观念,他们就能使之服从其统治。”这些捕手还表达了对受西方教育或影响的伊朗知识分子的不信任。“我们要这些满脑子腐朽思想的人有什么用呢?让他们到他们想要去的地方去吧!这些腐朽的家伙就是那些跟在西方模式后面亦步亦趋的知识分子,他们对我们的运动和革命毫无价值。”

具有这种观点的并不局限于年轻的激进派。许多持各种各样政治信仰的非西方人都具有这种观点。印度政治理论家梅达(VR·Mehta)在其颇具影响的著作《超越马克思主义:走向另一种前景》中提出,无论是西方的民主还是苏联的共产主义都不能为印度的发展提供合适的准则。他反对自由主义的民主,因为他认为这会把人贬低为生产者和消费者,从而导致一个自私自利的以个人为核心的社会。他也同样抵制共产主义,因为共产主义强调经济事务和国家活动,因而个人没有什么选择余地并且破坏了生活的丰富性和多样性。梅达因此得出结论说,“每个社会都有其自身的发展规律,都有充分发挥其功能的自己的道路。……支离破碎的印度社会不能以西方社会为榜样加以改造。印度必须找到适合其特殊情况的自己的民族建设和发展战略。”

反对西方的全球统治不足为怪。这种统治是一种历史的偏差,它由错综复杂的特定情况而产生,因而必定是暂时的。但是令人惊奇的是,当前地区自治的力量同样也正在主要的西方国家内兴起,一些已沉睡了几十年或几百年的民族群体或亚群体现在也活跃起来并要求自治。在美国,存在着少数民族群体,即黑人、操西班牙语者以及美洲土著居民。在邻近的加拿大,法裔魁北克人要求脱离的倾向已威胁到加拿大版图的统一。同样,英国正在对付苏格兰、爱尔兰和威尔士的所谓脱离主义者。法国也正面临着科西嘉、布列塔尼和巴斯克解放阵线的同样的挑战。

地区自治的要求并非仅仅针对西方的中央政权。在伊朗,对西方影响的普遍反抗与反对德黑兰中央政府统治的地方暴动——即由库尔德入、阿拉伯人、俾路支人以及土库曼人这些少数民族发动的叛乱齐头并进。由于这些少数民族几乎占到全国总人口的一半,伊朗百临地区自治要求的威胁远远超过来自任何西方国家的威胁。苏联也有类似的情况,那儿聚居着几十个非斯拉夫族的少数民族。由于他们的出生率大大高于斯拉夫族,他们同样很快将达到总人口的半数。苏联少数民族对政府不满的详细情况并不十分清楚。一位苏联逃亡来的历史学家安德烈·阿马尔里克(And-rei Amalrik)在其《苏联会生存到1984年吗?》一书中这样预测,少数民族将在苏联这个国家的瓦解中起到重要作用,而这是他满怀信心地期待和盼望着的。

我们时代的众多动乱均由两大互相对抗的力量之间的冲突而引起。一方面,由于现代通讯媒介、跨国公司以及环球飞行的宇宙飞船,现代技术正在前所未有地将全球统一起来。另一方面,全球又因那些决心创造自己未来的沉睡至今的大众的觉醒而正被搞得四分五裂。现代冲突这种历史性根源可以追溯到公元1500年以后的那几个世纪。在那几个世纪中,西方探险家和商人首次把全世界所有居民联系在一起。直到今天,我们仍然面临着这种决定性影响的积极面和消极面。埃及记者穆罕默德·海卡尔(Mohammed Heikl)写道:“陷入重围的民族主义已经集中精力,准备为了未来而不是过去而背水一战。”

Late 16th Century Sekta (North Carolina) Indian Village

Western ships arriving in Tianjin