Chapter 10 Chapter 8 Russian Expansion in Asia

At the same time that the Western Europeans were expanding overseas to the rest of the world, the Russians were on land expanding across Eurasia.Control of the vast landmass of Siberia was an epic saga comparable to America's westward drive toward the Pacific coast.In fact, the ever-advancing frontier left as lasting a mark on Russian character and Russian institutions as it did on Americans.

It should not be supposed that, among the nations of Europe, only the Russians are affected by a frontier.Much of Central and Eastern Europe was sparsely populated during the Middle Ages (see Chapter 2, Section 3).For centuries, the various peoples of Europe, especially the Germans, pushed their colonial boundaries along the Baltic coast and eastward along the Danube.But, as the Middle Ages came to an end, this internal colonization ceased to be a dominant theme.It was replaced by overseas colonization, and the peoples of Western Europe concentrated their energies on opening up and exploring the new frontiers of the New World.On the contrary, the Russians continued to expand overland into the vast European plains that stretched out from their doorsteps.This gigantic enterprise was carried on rapidly for centuries until the last Muslim Khanate in Central Asia was conquered in 1895.It is not surprising, then, that frontiers have been a major factor throughout Russian history, as they have been throughout American history.This chapter examines the nature and process of Russian expansion into Siberia and Ukraine.

In order to understand the astonishing expansion of the Russians across the Eurasian plains, it is necessary to understand the geography of these plains.When you open the map, the first thing you see is their staggering size.Indeed, Russia is associated with vastness—infinity.There is an agricultural proverb that says, "Russia is not a country; it is a world." This world includes one-sixth of the earth's land surface and is larger than the United States, Canada, and Central America combined.As night falls in Leningrad on the Baltic coast, dawn breaks in Vladivostok on the Pacific coast.The distance between the two cities is 5,000 miles, and the distance between New York and San Francisco is 3,000 miles.This contrast should be kept in mind when examining Russian expansion to the east and American expansion to the west.

Another striking feature of the vast Russian landmass is its astonishing topographical uniformity.It is, for the most part, a flat plain.The Ural Mountains do run across these plains in a north-south direction; they are generally believed to have divided Russia into two separate and distinct parts—European Russia and Asiatic Russia.But the truth is that the Urals are just a long, long, eroded range of mountains with an average height of only 2,000 feet, and they no longer extend as they meander southward at 51°N latitude, leaving a wide, The flat desert area is the gap.In these cases, the entire plain area must be seen as a geographic unity—the subcontinent of Eurasia.This topographical uniformity helps explain why the Russians were able to expand so quickly throughout the region, and why it remains under Moscow's control to this day.If we want to draw a dividing line across the Eurasian Plain, then this dividing line should not run vertically from north to south along the Ural Mountains, but from east to west, separating Central Asia, which has desert and semi-desert environments in the southeast, and forests in the north. It is distinguished from the frozen original Siberia.

The Eurasian Plain, which includes most of contemporary Russia, is surrounded by a natural border stretching from the Black Sea to the Pacific Ocean.This border consists of a continuous series of mountains, deserts and inland seas - it starts from the Caucasus Mountains in the west, and in the east it is followed by the Caspian Sea, the Ustyurt Desert, the Aral Sea, the Kyzyl Kum Desert, the Xing The Kush Mountains, the Pamir Mountains, the Tian Shan Mountains, the Gobi Desert, and finally the Greater Khingan Mountains stretching east to the Pacific Ocean.The ring of mountains surrounding the Eurasian Plain blocks wet winds from the Pacific Ocean and warm monsoons from the Indian Ocean; this explains the desert climate of Central Asia and the cold, dry climate of Siberia.The entire vast Siberia, from the Baltic Sea in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east, has essentially the same continental climate: short, hot summers and long, bitterly cold winters.The uniformity of climate facilitated Russia's eastward expansion as much as that of topography, for the frontier explorers felt the same comfort throughout the 5,000 miles east to west of the plain.However, frontier developers found that the Central Asian desert is strange and terrifying.They also found that these deserts were occupied by militarily powerful Muslim khanates, distinct from the weaker tribes of Siberia.As a result, the Russians did not control the Central Asian desert until 250 years after they reached the Pacific Ocean farther north.

Russian expansion was influenced not only by terrain and climate, but also by river systems.Due to the flatness of the terrain, Russian rivers are generally long, wide and free from turbulence.As such, they were invaluable as routes and vehicles for trade, colonization and conquest.In addition, they are suitable not only for sailing in boats in summer, but also for sledding in winter.To the west of the Ural Mountains, the famous rivers are the West Dvina, which flows into the Baltic Sea, the Dniester, Dnieper, and Don rivers, which flow south into the Black Sea, and the Volga, which flows first east and then south into the Caspian Sea.East of the Ural Mountains, the four major rivers that irrigate the Siberian Plain are the Ob River in the west, the Yenisei River in the center, the Lena River in the northeast and the Amur River in the southeast.As all of Siberia slopes down from the huge Tibetan plateau, the first three of these rivers flow north into the Arctic Ocean, while the fourth flows east into the Pacific Ocean.The fact that the Ob, Yenisei, and Lena rivers have their outlets in the Arctic Ocean largely negates their economic utility.The fact remains, however, that these rivers, with their many tributaries, provided a natural network of arteries stretching all the way to the Pacific Ocean, once the Russians crossed the Ural Mountains.It can be transferred from one waterway to another without much portage.so.They zigzag their way eastward, hunting furred animals.

A final geographical factor affecting the speed and course of Russian expansion was the combination of soil and vegetation present in the various regions of Russia.There are four main types of soils - a vegetation band runs parallel across Russia from east to west.In the far north, along the coast of the Arctic Ocean, lies a barren tundra that remains frozen year-round except for a six to eight-week growing period in summer.During the growing season, the sun never sets, giving brief but exuberant life to countless wildflowers - violets, daisies, forget-me-nots, daffodils and blueflowers.

To the south of the glacial belt is the taiga forest belt.It is the largest of the four vegetation regions, 600 to 1,300 miles wide and 4,600 miles long, accounting for one-fifth of the world's total forest area.In its northern zone, conifers and birch dominate the forests; further south, there is a mix of elms, aspens, aspens and maples.The Russians felt so at home in these forests that they could traverse all of Eurasia without ever losing this familiar protective cover.Many Russian writers have written about the beauty of their forests and what they meant to their people.The following quotation from Gorky's novel is very representative:

At the southern edge of the forest belt, the forest thins out and the trees grow dwarfed until they give way entirely to open, treeless savannah.Here, you can see fertile black soil formed by thousands of years of rotting grass.Today it is Russia's breadbasket, but for centuries it has been a source of misery and disaster.The steppes were once the home of nomads who raided on horseback in central Eurasia.When these nomads were strong enough, they struck out along the lines of least resistance—often westward into central Europe or eastward into China.Their attacks against the vulnerable Russians in Eastern Europe were more frequent.An important theme in Russian history has been this ongoing conflict between the Slav peasants of the forest and the Asian nomads of the steppe.At first the nomads won, and the result was two centuries of Mongol rule over Russia.But in the end, the Slavic inhabitants of the forest became strong enough not only to win their own independence, but also to expand beyond the Eurasian plain.

The fourth area, the desert area, is the smallest area, starting from China and extending westward only to the Caspian Sea.We already know that, for a variety of reasons—the lack of access, the harsh climate, and the military prowess of the native peoples—the desert region was not engulfed by the waves of Russian expansion until the end of the nineteenth century.

About 1500 years ago, the Russians pushed eastward from their sources in the upper regions of the Transnistria, Dnieper, Neman and Dvina rivers.They fanned out in a huge arc from their origin, and under the call of the vast plain, they continued to advance to the coast of the Arctic Ocean in the north, the Black Sea in the south, the Ural Mountains in the east and beyond.The Russians who migrated to the east or northeast remained under the shelter of the forest.They encountered little resistance in the forest areas—there were only scattered, loosely organized Finnish tribes; whom they either intermarried with or easily drove away.

These early Russian colonists combined agriculture and forestry.The ratio between agriculture and forestry depends on the location.In the northern woodlands, the coniferous forests, agriculture was of secondary importance because of the harsh climate, poor soil and little open space.Thus, the colonists of this zone spent most of their time trapping animals, fishing, and collecting beeswax, honey, resin, potash, and other forest by-products.Further south, in the mixed forest zone, farming is the main activity.The colonists still depended largely on the forest for its various resources, but more time was spent cultivating it.Rye is the main crop, however barley, oats, wheat, flax and hemp are also grown.The main method of cultivation is temporary sowing on the ashes of forests or scrublands cleared by fire, or in occasional clearings of desolate grasslands.After several years of planting, these clearings were either abandoned, returned to wasteland, or kept as rough pastures until their productivity was restored.The practice, reminiscent of the backwoods of the Americas, is primitive and wasteful, but it doesn't matter much because the forest continues endlessly.

In these cases, scattered homes and small village roots were the general rule—there were no centralized villages or cities.The few towns that did exist developed as centers of trade along major waterways.This was the case for Kyiv on the Dnieper River, which was responsible for north-south traffic, and Novgorod on the shore of Lake Ilmen, which controlled east-west trade.It was long-distance trade that provided the basis for the development of the first Russian state in the ninth century AD.Kyiv was the center of the country, but the country remained a loose confederation of principalities along the waterways.Kyiv itself was extremely vulnerable due to its location on the border between the forest area and the steppe.Thus, it had to wage a constant struggle for survival against nomadic cavalry.Certain powerful rulers of Kyiv were able to claim power from time to time as far as the Black Sea in the south and the Dozi River in the west.But this display of strength was short-lived; the Russian colonists were unable to settle beyond 150 miles south and east of Kyiv because the threat of nomadic invasion hung over their heads like the sword of Damocles.

In 1237, the sword came; the Mongols swept through Russia as they swept across most of Eurasia.Before the Mongol invasion, Kyiv was described by travelers as a grand metropolis of sumptuous palaces, eight markets and 400 churches, including St. Sophie's Cathedral.However, eight years after the invasion, when the Franciscan monk Joannis di Plano Kapini passed through Kyiv on his way to the Mongolian capital, he found that the former capital had only 200 residences, and the capital was surrounded by corpses. .

The Mongols continued to push their devastating aggression into central Europe, right at the gates of Italy and France.Then they retreated automatically, leaving only the Russian part of Europe.Their vast empire, which spread in all directions, did not long survive as a unity.It was split into regional parts, the so-called Golden Horde including Russian regions.The capital of the Golden Horde, and the capital of Russia for the next two centuries, was Sarai, near present-day Stalingrad.Thus the age-old struggle between forest and steppe was decisively resolved with the victory of the steppe and its nomads.

The Russians now surrendered some of their small enclaves in the steppe and retreated deep into the forest.There, as long as they recognized the Khan's suzerainty and paid tribute to the Khan every year, they could live in their own way.Gradually, the Russians regained their strength and developed a new national center—Moscow Park, deep in the forested area far from the dangerous steppes.Apart from being less accessible to nomads, Moscow had other advantages.It is located at the intersection of two traffic arteries leading from the Dnieper River to the Northeast.Since many large rivers flowing in different directions pass through the Moscow region and are closest to each other, Moscow benefits from an inland water system.The park also enjoyed the advantages of its series of peaceful, frugal, and calculating rulers.These rulers patiently and relentlessly increased their holdings until Moscow became the new national nucleus. At the beginning of the 14th century, the area of the duchy was about 500 square miles, but by the middle of the 15th century, it had grown to 15,000 square miles.A century later, during the reign of Ivan the Terrible (reigned ID33-1584), all Russian parks were brought under the rule of Moscow.

The "growth of Russian lands" completely changed the balance of power between the Russians and the Mongols, then more commonly known as the Tartars.Originally, the Tatars won because they were very different from the strife-ridden state of Kyiv, they were united internally, and they also had a fast-moving cavalry force and were militarily more advanced.However, by the 16th century, the Russians were unified under Moscow, and the Golden Horde, apart from the Khanate of the Siberian Tatars in the east of the Ural Mountains, was split into the Kazan Khanate and the Astrakhan Khanate And the three hostile countries of the Crimean Khanate.Also, Russian military technology was advancing as they benefited from the great advances made in Western Europe, especially in musketry and artillery. When Ivan attacked the Tatars in Kazan in 1552, his superiority in artillery, combined with the assistance of a Danish technician who oversaw the bombing of the Kazan fortress walls with mines, proved decisive.After the mines exploded, the Russians managed to quickly capture the fortress and then the entire Kazan Khanate.They swept down the Volga, sweeping the basin, and easily captured Astrakhan in 1556.In order to consolidate the occupied territory, the Russians built a series of fortified strongholds on the banks of the Volga River, all the way to the mouth of the Volga River in Astrakhan.The Russians thus became masters of the vast Volga valley, reaching the Caspian Sea to the south and the Ural Mountains to the east.

At this time, the way was opened for unlimited Russian expansion beyond the Volga and the Ural Mountains.Some new territories were won by force, as was the case with Siberia.This type of expansion is discussed in the next two sections.Still others were acquired through personal deals with native chiefs in the same way that Europeans bought Manhattan Island and large tracts of land along the Ohio and other major rivers from American Indians.The famous Russian writer Sergey Aksakov vividly described the expansion of this method in his memoir "A Russian Gentleman":

The victory of the Russians made the Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan cease to exist.However, Crimea and the Tatars on the other side of the Ural Mountains remained independent and continued to harass the Russian colonists with constant raids.For reasons discussed later in this chapter, the Russians had to be ravaged by the Crimean Tatars until the end of the eighteenth century.However, they could easily wipe out the Siberian Khanate, and in doing so, unknowingly began their epic march to the Pacific coast.

It was mainly bold and capable frontier developers called Cossacks who crossed the Ural Mountains and conquered Siberia.These people resembled the frontier developers of the American West in many ways.Most of them were former peasants who had fled Russia or Poland to escape the yoke of serfdom.Their refuge was the barren grasslands to the south, where they became hunters, fishermen, and herders.Just as America's frontier settlers became half-Indians, so they became half-Tatars.They love liberty and equality, but are capricious and robbing; they are ready to be bandits and robbers whenever it seems profitable.The famous Russian novelist Gogol gave a vivid description of the life style of the Cossacks as follows:

A typical product of this frontier environment was Yermak Tsimofeyevich; he was the son of a Don Cossack and a Danish slave girl, with blue eyes and a red beard.At the age of 24, he was sentenced to death for stealing a horse, so he fled to the Volga River and became the leader of a band of robbers on the river.He indiscriminately plundered Russian ships and Persian caravans until government troops arrived to encircle them.So he led his group of people to flee up the Volga River to the Kama River, a tributary upstream.In the valley of the Kama River, a wealthy merchant named Grigory Stroganov had been granted concessions to large tracts of land there until then.Stroganov struggled to carve out his territory, but was repeatedly frustrated by attacks from nomads from the other side of the Ural Mountains.These attacks were organized by the blind Guchu Khan, the Muslim military chief of the Siberian Tatars.Faced with this predicament, Stroganov welcomed Yermak and his men and hired them to defend the colony.

The robber Yermak now showed that he had the qualities of a builder of a great empire.What Pizarro and Cortes had done for Spain in America, he had done for Russia in Siberia.Yermak, with the boldness of a conqueror, decided that the best defense was an offense. On September 1, 1581, he set out with 840 people and went deep into Guchu Khan's homeland to attack him.Yermak, like the Spanish conquistadors, enjoyed the great advantage of good weapons.He was well equipped with muskets and cannon that terrorized the natives.Although Gu Chu had received information that the invaders could direct thunder and lightning to pierce the strongest Qinyujia, he still fought desperately to save his capital Sibir.He gathered 30 times the strength of the Yermak army and sent his son Mametkul to command the defense.The Tatars fought doggedly behind felled trees, holding off the advancing Russians with showers of arrows, and seemed to gradually gain the upper hand.However, at a critical moment, Mametkul was wounded and the Tatar army was left without a leader.Gu Chu, who was blind, fled south in despair, and Yermak occupied his capital.The Russians then gave the name of this capital city to the whole region east of the Ural Mountains, which began to be called Sibir, Siberia in English.

Yermak reported the results of the expedition to Stroganov and wrote directly to Tsar Ivan the Terrible, asking for forgiveness for his past crimes.The Tsar was very happy to learn of Yermak's achievements, and canceled all the sentences against him and his subordinates, and also showed him special favors, bestowing on him an expensive fur from his shoulders and two sets of richly decorated armor , a goblet and a lot of money as gifts.Yermak now displayed the foresight of an empire-builder trying to establish commercial relations with Central Asia.He sent missions as far as the ancient city of Bukhara.However, Yermak was doomed not to live to complete his ambitious plan.Old Guchu in the south has been inciting fierce nomads against the Russians. On the night of August 6, 1584, one of his shock troops attacked Yermak and his companions while they were sleeping on the banks of the Irtysh River.Yermak fought to the death for his life and tried to escape by swimming across the river.According to legend, he drowned because of the heavy armor given to him by the Tsar.

Despite this victory, the Tartars were fighting an impossible battle.Their enemy was too strong, and they could not push the enemy back west of the Ural Mountains.Even Gu Chu eventually realized the futility of further resistance and offered to surrender.With his surrender, the first phase of the Russian advance into Siberia came to an end.The way to the Pacific coast was opened.

The impression Yermak's exploits made on the populace is reflected in a folk song describing his adventures.The following two verses describe Yermak's admonitions to the Cossacks before the expedition, and also indicate his relationship with the Tsar:

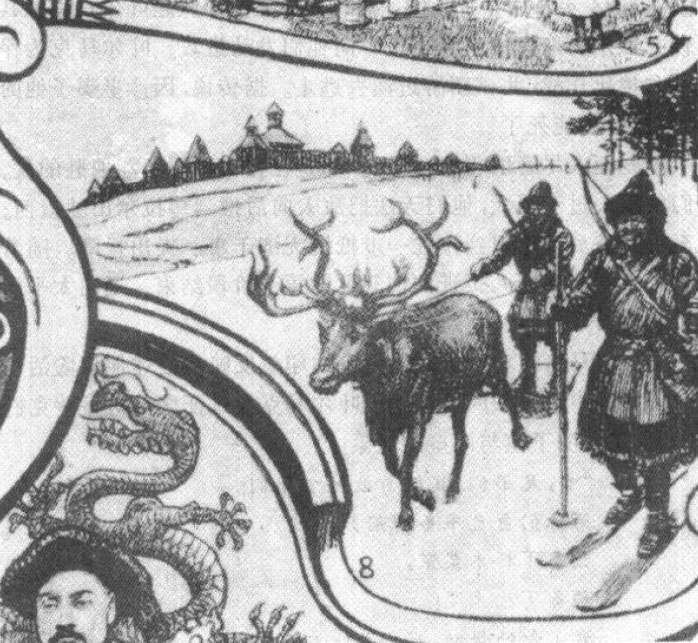

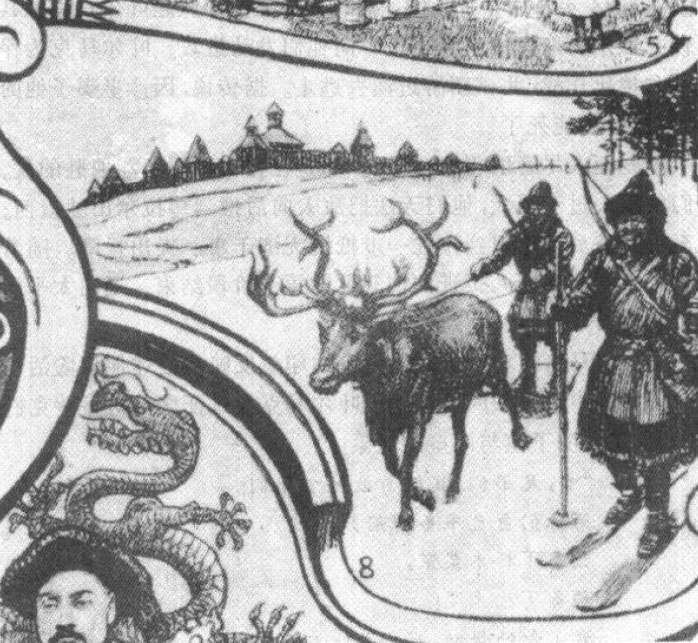

Siberian tribesmen traveling by reindeer and sleigh.In the background is a Russian fortress

Russia's conquest of Siberia was a remarkable achievement.The Russians in Siberia, like the Spaniards in America, won a vast empire in a few short years with astonishingly small forces.Facts have proved that the Irtysh Khanate in Guchu is just a weak shell with no solid inside.Once the shell is punctured.The Russians would then be able to travel thousands of miles without encountering serious confrontation.Their speed of advancement is staggering.Yermak campaigned between 1581 and 1584.Sir Walter Raleigh also landed on Roanoke Island in North Carolina in 1584.By 1637, within half a century, the Russians had reached the Sea of Okhotsk in the Pacific Ocean, covering more than half the distance between the Pacific coast and the Atlantic coast of the United States, while the British colonists had not yet crossed Ale The other side of the Gurney Mountains.

The rapidity of the Russian advance can be explained by various factors.As we already know, climate, topography, vegetation, and river systems all favored invaders.Indigenous peoples are disadvantaged by their small numbers, poor weapons, lack of unity and organization.In addition, the stamina and courage of the Cossacks should be taken into account; they, like the illegal fur hunters of French Canada, endured great hardship and danger in the wilderness.The reason they do this can be summed up in one word - "fur".The sable fur lures them from one river to another by overland transport, and so on eastward.

As the Cossacks advanced, they built fortified strongholds or fortresses like the fortresses in the outlying regions of America to protect the communication between them.The first fortress in Siberia was built at Tobolsk, near Sibir, at the confluence of the Tobol and Irtysh rivers.When the Russians discovered that these two rivers were tributaries of the Ob, they rowed down the Ob, only to find themselves carrying their boats some distance overland into the Yenisei, the next great waterway.By 1610, they had reached the Yenisei River Basin in large numbers and established the Krasnoyarsk fortress.Here they encountered the Buryats, a warlike people who had resisted them for the first time since the conquest of ancient Chu.Avoiding the Buryats, the Russians turned to the northeast and found the Lena River. There they established the Yakutsk fortress in 1632 and traded lucratively with the native, moderate Yakuts.However, the Buryats continued to attack their lines of communication, and as a result, the Russians waged a savage war of extermination.In the end, the Russians won and pushed on to Lake Baikal; there, in 1651, they established the fortress of Irkutsk.

During this period, expedition after expedition has traveled in all directions from Yakutsk. In 1645, a group of Russians reached the shores of the Arctic Ocean.Two years later, another group of people arrived on the Pacific coast and established the Okhotsk fortress.The following year, 1648, the Cossack explorer Simino Dezhnyov set off from Yakutsk on a remarkable journey.He sailed down the Lena River.He found some stretches of river so wide that he could not see the banks; deltas the size of continents filled with the rubble of a watershed.After passing the delta, Dezhnyov sailed east along the coast of the Arctic Ocean until he reached the true tip of Asia.He then sailed down a waterway that came to be known as the Bering Strait.After losing two ships in a storm, he reached the Anadyr River; there he established the fortress of Anadyr, no less than 7,000 miles from Moscow!Dezhnyov sent a report on his trip to the governor in Yakutsk; the governor filed the report and forgot about it.The report was not rediscovered until after the official expedition of Vitus Bering; Bering sailed in 1725 to determine whether America and Asia were connected by land—a question that Dezhnyoff had 77 Years have been excellently resolved.

So far, the Russians have not encountered any force that can stop them.However, as they advanced from Irkutsk to the Amur Valley, they encountered not only opponents, but also outposts of the powerful Chinese Empire, which was then at the height of its power (see Chapter 4, p. Section II).

Hunger drove the Russians to the Amur Valley.The frigid north produced furs rather than food, and the barns of European Russia seemed to be on another planet.Therefore, with hope, the Russians turned south to the Amur River Valley; according to indigenous legends, it is an excellent place with fertile soil and golden yellow grains.Cossack Vasily Boyarkov received the task of opening a trail from the Lena to the Amur.His extraordinary expedition, together with Dezhnyov's trip to the Arctic coast, holds a prominent place in the history of Siberian exploration.

Boyarkov set out from Yakutsk with 132 people on June 15, 1643.Up the Lena and its tributaries, he crossed 42 rapids at one point, losing one boat.After spending the winter on the way, he went down the Amur River the following year.When Boyarkov reached the Songhua River, he sent local men to explore this tributary.All but two of the group were ambushed and killed a day later.The main force reached the mouth of the Amur River, where they passed the winter with terrible hardships due to the cold and lack of food.In the spring of the following year, they boldly sailed into the open sea in small boats.They headed north along the coast to the Sea of Okhotsk before returning to Yakutsk by land.Eighty members, nearly two-thirds of the original expedition, perished during the three-year, 4,000-mile journey.Boyarkov brought back 480 sable pelts and wrote a report in which he declared the conquest of the Amur River feasible.

A succession of adventurers followed Poyarkov into the Amur valley.They captured the city of Albazin, built a series of fortresses, and slaughtered and looted in a typical Cossack way.These atrocities they committed on the fringes of China eventually so enraged the Chinese emperor that he sent an expedition north in 1658.The Chinese recaptured Albazin and cleared the Russians from the entire Amur valley.However, as soon as they evacuated, the Russian adventurers returned in droves.As a result, another Chinese army was sent to the Amur River, while the two governments began negotiations to resolve the border issue.After much debate, the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed on August 27, 1659.

In addition to its extremely important provisions, this treaty is also of special importance for two issues: it is the first treaty signed between China and a major European power; since the Chinese delegation has Jesuits as interpreters, the treaty is written in Latin. drawn up.The border was established along the Trans-Xingan Mountains north of the Amur River, so the Russians had to withdraw completely from the disputed basin area.In return, the Russians were granted commercial privileges by Article IV, which stated that the subjects of both countries were free to buy and sell across the frontier without interference.The trade that developed in later ages was by caravans and included gold and furs; the Russians exchanged gold and furs for tea.It was from the Chinese that the Russians got what would later become their national drink.The Russians quickly became even more tea drinkers than the British.

With the signing of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, the first phase of Russian expansion in Asia came to an end.For the next 170 years, the Russians have always abided by the treaty and stayed outside the Amur River Basin.They did not go south again until the middle of the nineteenth century; then they were much stronger than they had been in Vasily Poyarkov's time, and the Chinese were relatively weak.

Since Siberia was acquired by the Russians in successive waves of expansion in a short period of time, the Russian government would naturally see it as a whole and manage it as a whole.The government agency responsible for Siberian affairs is the Siberian Administration; it was first based in Moscow and then moved there when Peter the Great moved the capital to St. Petersburg in 1703.The administrative center was in Tobolsk, where it remained until 1763, except for a short break.That year, Catherine the Great divided Siberia into two regions whose administrative centers were located in Tobolsk and Irkutsk.This measure was necessary because the western regions of Siberia, which were closer to the motherland, developed faster than the farther eastern regions.

Throughout the 17th century, the fur trade dominated Siberia, even more so than it did the French colonies.The government is the main fur trader; in fact, furs are one of the government's most important sources of revenue.The government acquires furs by various means: it collects a tribute in the form of furs from the natives in the form of a tax, and it imposes a 10% tax on the best furs from Russian trappers and traders; The right to buy the best furs that natives and Russians have acquired.By 1586 the treasury had received 200,000 sable, 10,000 black fox, 500,000 squirrel and many beaver and mink skins from the various sources mentioned above.In addition, the government maintained a favorable monopoly on the foreign trade in furs.Estimates of revenues from Siberian furs in the mid-seventeenth century now range from 7% to 30% of the country's total income; the lower figure is probably closer to the truth.One of the most eminent scholars on the subject concluded that "the government maintained a large surplus from the fur trade in paying its administrative expenses in Siberia, and added a vast area to the country."

The effect of Russian expansion on the tribes of Siberia was as disastrous as that of American expansion on the North American Indians.On the one hand, the Moscow government repeatedly instructed officials to treat the natives "with generosity and kindness", and on the other hand, ordered these officials to "zealously seek the interests of the monarch."Since the promotion of officials was affected by the amount of furs they collected, it is understandable that the welfare of the natives was not given basic concern.One consequence of this system of fur tribute was that it inhibited the missionary movement of the Russian Orthodox Church.Since converts to Orthodoxy were not required to pay tribute, missionary work was permanently suspended as a luxury not afforded by the state coffers.As a result, Islam spread widely among the Tartar peoples on the southern fringes of the forest, as did Buddhist Lamaism among the Buryats of Mongolia.Thus we see that a fundamental difference between the Russian expansion in Siberia and the Spanish expansion in North and South America is the great difference in the degree of zeal with which Catholics and Orthodox Christians converted pagans.It is inconceivable that the Catholic Church would allow another religion to spread among those under its care in America.

In the 18th century, merchants and trappers began to give way to permanent colonists in the area west of the Yenisei.Some of the colonists were prisoners, and they were sent to Siberia, just as prisoners from Western European countries were shipped to America, Australia, and the French West Indies.Most of these prisoners were hardened criminals; however, a considerable number were also political prisoners, who formed some of the most educated and educated classes of society.There are also some colonists who have to go at the official call.Each region of European Russia must provide a certain number of farmers for the colonization of Siberia every year.These people enjoy certain tax exemptions and state assistance, so they can start life in the new environment.

Most of the permanent immigrants to Siberia were neither prisoners nor colonists who were forced to go, but peasants who moved there voluntarily to escape the bondage of creditors, military service, religious persecution, and especially serfdom. It is extremely important that the serfdom that developed and spread in European Russia in the 16th and 17th centuries never took root in Siberia.The reason seems to be that serfdom developed primarily to satisfy the needs of those aristocrats who were indispensable to the functioning of the state.However, nobility did not migrate to Siberia because Siberia did not have the same attractiveness as Moscow and St. Petersburg.Siberia thus avoided aristocracy, and thus, serfdom.Government decree does state that escaped farmers are returned to their owners.然而,西伯利亚地方当局对需要获得移民这一点的印象比对需要实施法律这一点的印象更深,常常庇护逃亡者。

1763年之前西伯利亚人口增长的情况可由以下数字得到说明:

值得注意的是,到1763 年,生活在西伯利亚的俄罗斯人仅42万,而北美英属13个殖民地的人口那时却已上升到150万至200万之间,大约为前者的四倍。换句话说,俄罗斯人先前在进行探险和征服时速度快得多,如今在移居殖民地时速度又慢得多。一个原因在于,西伯利亚只能靠俄国获得移民,而美洲殖民地却从欧洲好几个国家得到移民。甚至更重要的是,美洲对想要成为殖民者的人具有更大的吸引力。如果我们设想,沿美国的墨西哥湾海岸有一系列极高的山脉,挡住了来自南方的、饱含水分的暖风,那么,我们可以想象出西伯利亚环境的一些缺点。由此引起的寒冷和干旱正是前往西伯利亚的移民所不得不面临的。相反,如果他们当初发现一个可与大西洋沿岸或美国中西部各州的气候相媲美的气候,那么,西伯利亚无疑本会从俄国,甚至可能从更西面的国家,吸引来为数多得多的移民。事实是,西伯利亚的气候条件更类似于加拿大的气候条件。到1914年,这两个地区的人口大致相同——加拿大800万人、西伯利亚900万人,并不是偶然的,而美国,面积小于加拿大或西伯利亚,其人口至1914年却已增长到1亿。

我们前面已提到,16 世纪中叶,伊凡雷帝征服喀山和阿斯特拉罕,但还留下两个独立的汗国——南面的克里米亚鞑靼人的汗国和乌拉尔山脉另一边的古楚的鞑靼人的汗国。后者在短短几年中为叶尔马克及其后继者所征服。但是,克里米亚的鞑靼人一直坚持到18世纪末。他们得以幸存的一个原因是,他们享有奥斯曼帝国的强有力的支持。克里米亚汗国国都巴赫奇萨赖城中的可汗承认君士坦丁堡的奥斯曼苏丹的宗主权,并在战时向后者提供骑兵部队。作为回报,苏丹每当可汗受到基督教异教徒的威胁时,便给可汗以援助。此外,可汗通常能在对乌克兰大草原提出相冲突的要求的各种异教徒——俄罗斯人、波兰人和哥萨克人之间挑拨离间。

最后,可汗还因其领土的不易接近而得到巨大帮助。守卫克里米亚半岛的入口的彼列科普地峡离莫斯科的直接距离是700 哩,但骑马行走的实际哩数却多得多。最后300哩要穿过一种特别干旱的草原区;在那里,侵略军极难找到水和粮食。因而,俄罗斯人直到他们的拓居界线已大大地向南推进、为他们提供了一块帮助打过草原去的根据地时,才能对克里米亚的鞑靼人开展重大的军事行动。即使那时,彼得大帝在1687和1689年的对鞑靼人和土耳其人的战争中,仍不能成功地解决供应问题。

以上种种因素说明了为什么克里米亚汗国能幸存到18 世纪后期叶卡捷琳娜大帝在位时。从伊凡雷帝到叶卡捷琳娜大帝的250年,是黑海以北乌克兰草原上发生杀戮和混乱的年代。乌克兰是一块荒芜的无主地区;俄罗斯人、波兰人、哥萨克人和鞑靼人在那里打打停停地交战,并不时地改变彼此间的种种联合。鞑靼人的频繁的袭击特别具有破坏性,它们实际上是猎取奴隶的远征。鞑靼人“象骑在灵玃身上的猴子那样”伏身在马背上,沿着三条主要的小道行进,深深地侵入莫斯科中心地,去搜寻强壮的男人、妇女和孩子。研究俄国历史的英国权威人士伯纳德·佩尔斯爵士生动地描写了这种由鞑靼人带来的灾难的性质:

1571年,鞑靼人烧毁了莫斯科本身。但是,1591年以后,他们再也没有成功地渡过莫斯科前面的奥卡河,而且渐渐地,他们远远侵入北方的次数愈来愈少。不过,数百人一伙的小队人马还是继续骚扰俄罗斯农民,他们悄悄溜入他们看出有良机的地方,然后带着劫来的人迅速地撤走。

终于,叶卡捷琳娜大帝能从俄国边上除去鞑靼人这根刺。她所以能在其如此多的前任失败过的地方取得成功,是因为有几个对她有利的因素在起作用。一个因素是,波兰和土耳其这两个以往一向与俄国争夺对乌克兰的所有权的强国迅速衰落了,而俄国,一方面由于其惊人的领土扩张,一方面由于其强固的中央集权制政府,正在稳步地变得更加强大起来。俄国的力量在叶卡捷琳娜统治期间特别有效,因为女皇是一位极好的外交家,巧妙地利用了国际形势所提供的每一机会。女皇与奥地利的约瑟夫二世和普鲁士的腓特烈大帝分别缔结协约;这些协约使她能在不和欧洲任何主要强国发生纠葛的情况下,放手进行对土耳其的战争。叶卡捷琳娜还具有选拔第一流的顾问和将军的才能。最杰出的是亚历山德·苏沃洛夫将军,他是一位敌得上拿破仑的军事天才,是执行叶卡捷琳娜的政策的无与伦比的工具。此外,在从彼得大带发动战争以来的80年中,俄国农民谨慎、耐心地把他们的拓居界线向南推进,因此,苏沃洛夫得到了一个比彼得所曾有过的更坚固的作战基地。

叶卡捷琳娜对鞑靼人和土耳其人发动了两次战争。第一次战争在1768 至1774年间,使俄国有效地控制了克里米亚半岛。1774年的库楚克-凯纳吉条约割断了巴赫奇萨赖与君士坦丁堡之间的联系,并使俄国获得了克里米亚半岛上的几个战略据点。第二次战争是从1787至1792年,同第一次战争一样,以苏沃洛夫所赢得的辉煌胜利为标志。实际上,苏沃洛夫的胜利之巨大,已引起一些困难,因为普鲁士和奥地利对俄国朝地中海的势不可挡的推进惊恐起来。不过,叶卡捷琳娜机敏地利用了法国革命的爆发,她向奥地利和普鲁士的统治者指出,巴黎的革命运动比起俄国在近东的扩张,是一个大得多的危险。因而,叶卡捷琳娜能把她对土耳其人的战争坚决进行到1792年土耳其人接受推西条约时。这一条约使俄国获得了从东面的库班河到西面的第聂伯河的整个黑海北岸。

整个乌克兰这时已在俄国的统治之下,森林终于战胜了大草原。中亚的沙漠区仍在坚持不屈,但它也注定要在下一世纪中受到莫斯科的统治。国际形势所提供的每一机会。女皇与奥地利的约瑟夫二世和普鲁士的腓特烈大帝分别缔结协约;这些协约使她能在不和欧洲任何主要强国发生纠葛的情况下,放手进行对土耳其的战争。叶卡捷琳娜还具有选拔第一流的顾问和将军的才能。最杰出的是亚历山德·苏沃洛夫将军,他是一位敌得上拿破仑的军事天才,是执行叶卡捷琳娜的政策的无与伦比的工具。此外,在从彼得大带发动战争以来的80年中,俄国农民谨慎、耐心地把他们的拓居界线向南推进,因此,苏沃洛夫得到了一个比彼得所曾有过的更坚固的作战基地。

叶卡捷琳娜对鞑靼人和土耳其人发动了两次战争。第一次战争在1768 至1774年间,使俄国有效地控制了克里米亚半岛。1774年的库楚克-凯纳吉条约割断了巴赫奇萨赖与君士坦丁堡之间的联系,并使俄国获得了克里米亚半岛上的几个战略据点。第二次战争是从1787至1792年,同第一次战争一样,以苏沃洛夫所赢得的辉煌胜利为标志。实际上,苏沃洛夫的胜利之巨大,已引起一些困难,因为普鲁士和奥地利对俄国朝地中海的势不可挡的推进惊恐起来。不过,叶卡捷琳娜机敏地利用了法国革命的爆发,她向奥地利和普鲁士的统治者指出,巴黎的革命运动比起俄国在近东的扩张,是一个大得多的危险。因而,叶卡捷琳娜能把她对土耳其人的战争坚决进行到1792年土耳其人接受推西条约时。这一条约使俄国获得了从东面的库班河到西面的第聂伯河的整个黑海北岸。

整个乌克兰这时已在俄国的统治之下,森林终于战胜了大草原。中亚的沙漠区仍在坚持不屈,但它也注定要在下一世纪中受到莫斯科的统治。

Siberian tribesmen traveling by reindeer and sleigh.In the background is a Russian fortress