Chapter 2 preamble

Any preface should be written concisely; however, this preface should be a space container, a spaceship, which will carry the reader to the moon, so that he can observe the whole picture of the earth, just like the chapters after this preface let the reader understand to the major events on Earth.

A global approach to the study of history is not new.In fact, it signifies the revival of the historiographical tradition of the Age of Enlightenment, in which the sense of world history was as compatible with prevailing views of progress as was required at the time.Before the Age of Enlightenment, Western historians were constrained by the need to fit all known historical events into a rigid biblical framework.They used to divide the past into several historical periods corresponding to the four world empires of Adar, Persia, Greece and Rome prophesied in the Book of Daniel.By the late seventeenth century, however, this traditional division became increasingly inappropriate in the face of new historical data on China and India.It was Voltaire's Discourse on the Customs and Spirits of Nations (1752) and the multivolume History of the World (1736-1765) that first clearly broke with this old mode of world history compilation; Several traditional areas of antiquity in the Bible, China, India, and the Americas are also discussed.

However, by the end of the 18th century, interest in global history began to fade.The emergence of a more scientific concept of history established a standard of authenticity and reliability of data, which was not available when discussing civilizations other than Greek and Roman civilizations.Perhaps a more important reason for the narrow vision of historiography was due to the rise of the belligerent nation-state, which drove the writing of nation-state histories rather than the previous world histories.This historiography, limited to the history of nation-states, prevailed at least until World War I, and to a large extent until World War II.

Over the past few decades, though, there has been a revival of interest in world history.Continuous advances in historical research have now greatly expanded the range of reliable sources, while the effects of two world wars and the scientific and technological revolution, along with rapid advances in communications, have forced the general recognition of the fact of "one world".Demonstrating this new historiographical tendency are H. G. Wells's Outline of World History (1919), Ralph Turner's The Great Cultural Traditions (1941), William H. McNeil's The Rise of the West, A Social History of Humanity (1963) and the contemporary UNESCO Journal of World History and History of Humanity.

The reason this new interest has so far had little impact on classroom instruction is apparently due to doubts about the practicality of teaching world history.If the common view is that the history of the world is the sum of the history of all countries or all civilizations in the world, then the above doubts are completely justified.Of course, this view is completely absurd.As far as modern European history is concerned, it is not, after all, the history of England, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, the Scandinavian countries, the Balkans, and the Baltic states in sequence.Rather, while it deals with basic developments within the major states, it is equally important to deal with those forces or movements that had an impact on the entire continent.The same is true for modern world history courses, although the purpose is to analyze the basic characteristics and development of major regions of the world, but it is also important to study those forces or movements that have influenced the entire world.Therefore, the problem now is not that the world history course involves a lot of historical facts, but that the perspective of observation is different, that is, the world history course tells history from a global perspective rather than from a regional or national perspective.

If we examine the early modern period from the voyages of Columbus to the outbreak of the French Revolution, the meaning of different observation angles may be specifically explained.In European history classes, for the early modern period, the main topics are usually nothing more than: dynastic conflicts, Protestant resistance, and overseas expansion in the 16th century; the Thirty Years War in the 17th century, the rise of the absolute monarchy, and the British Revolution; dynastic and colonial wars, the Enlightenment, enlightened despots.

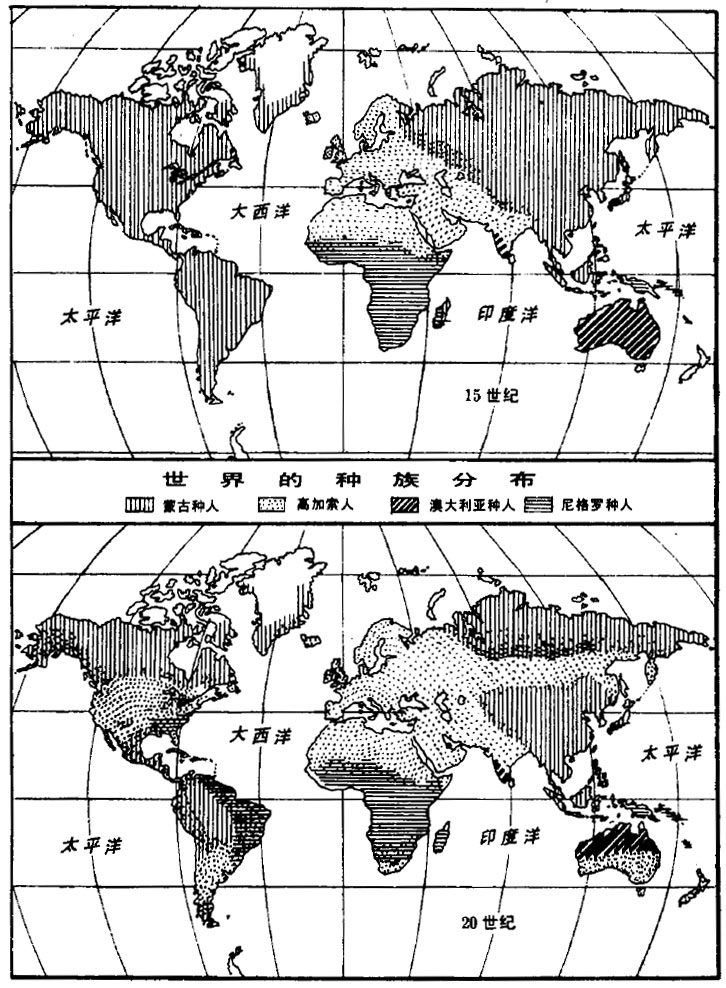

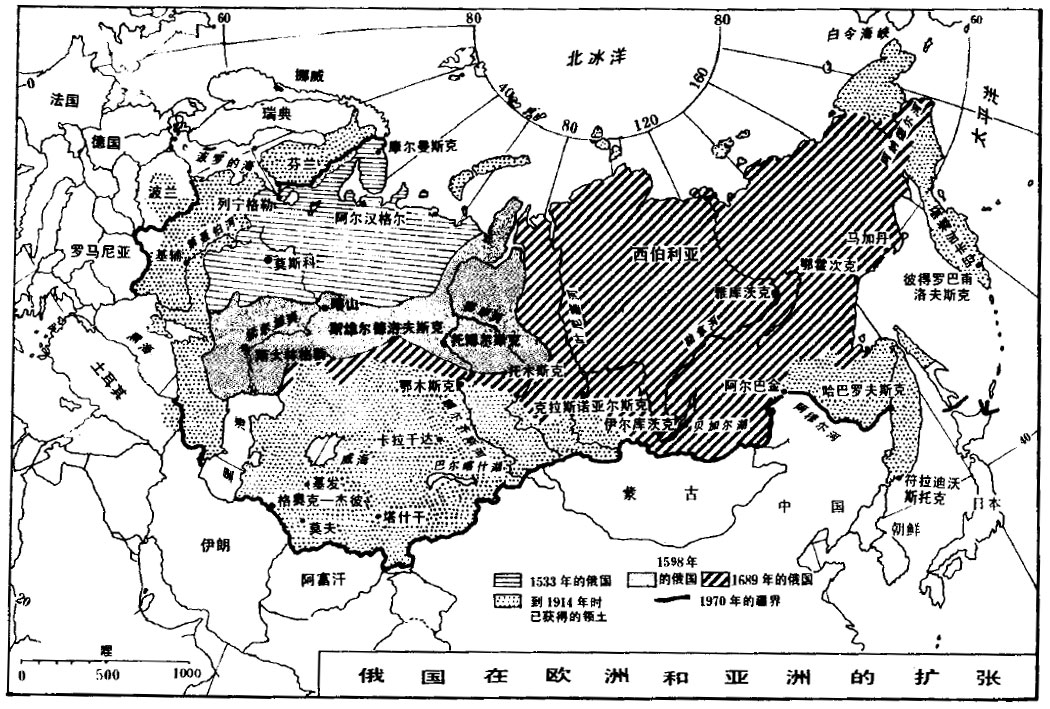

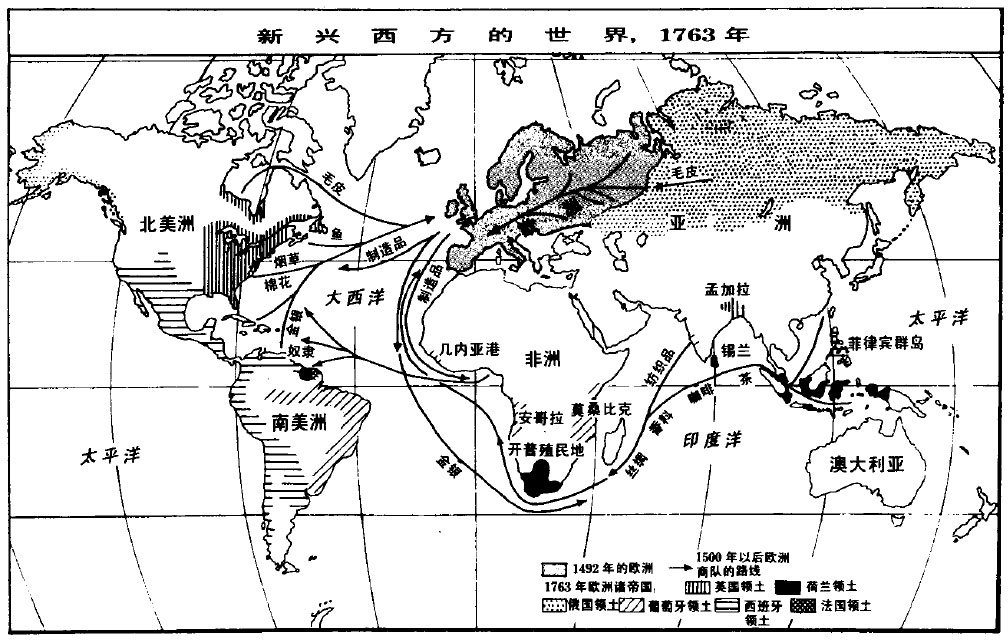

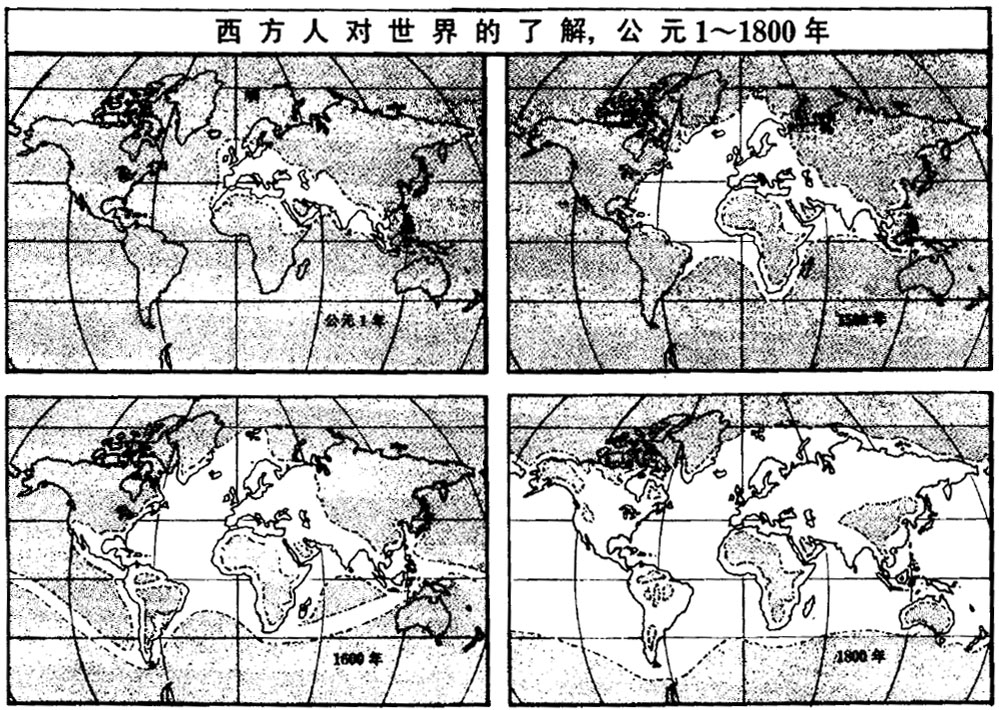

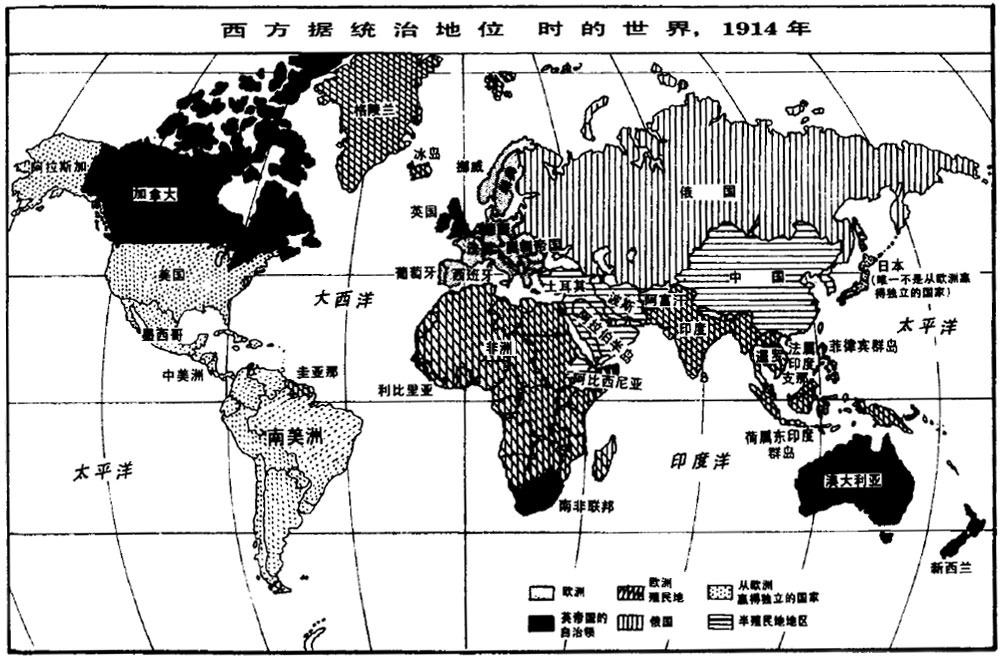

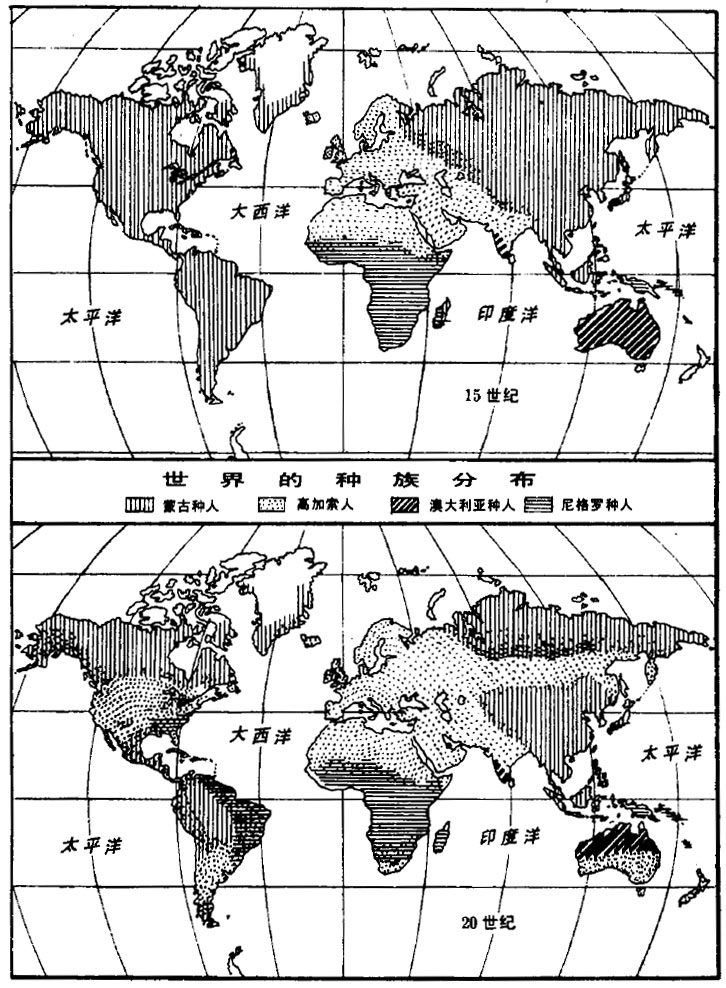

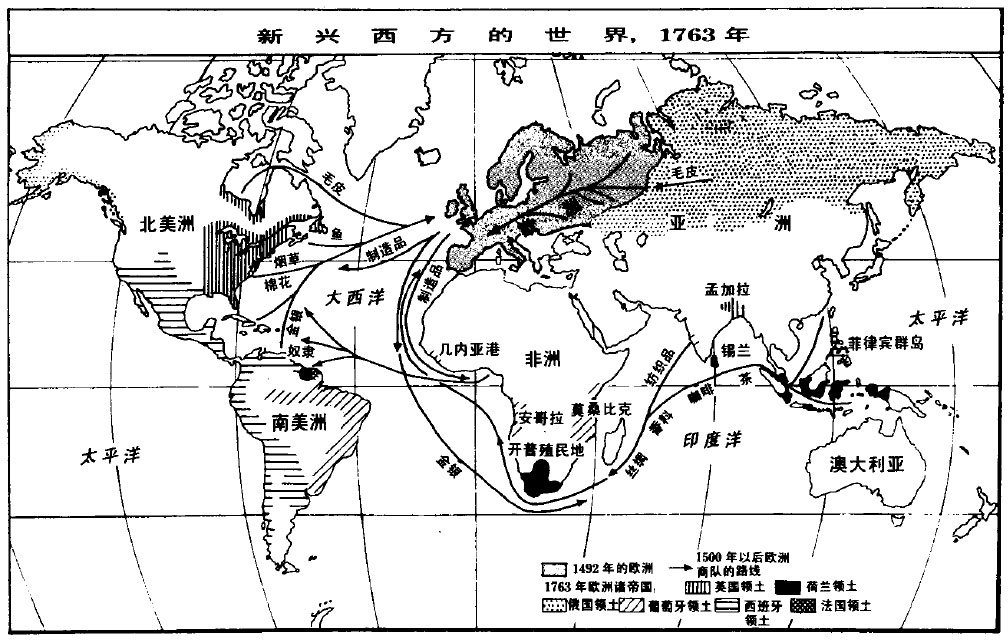

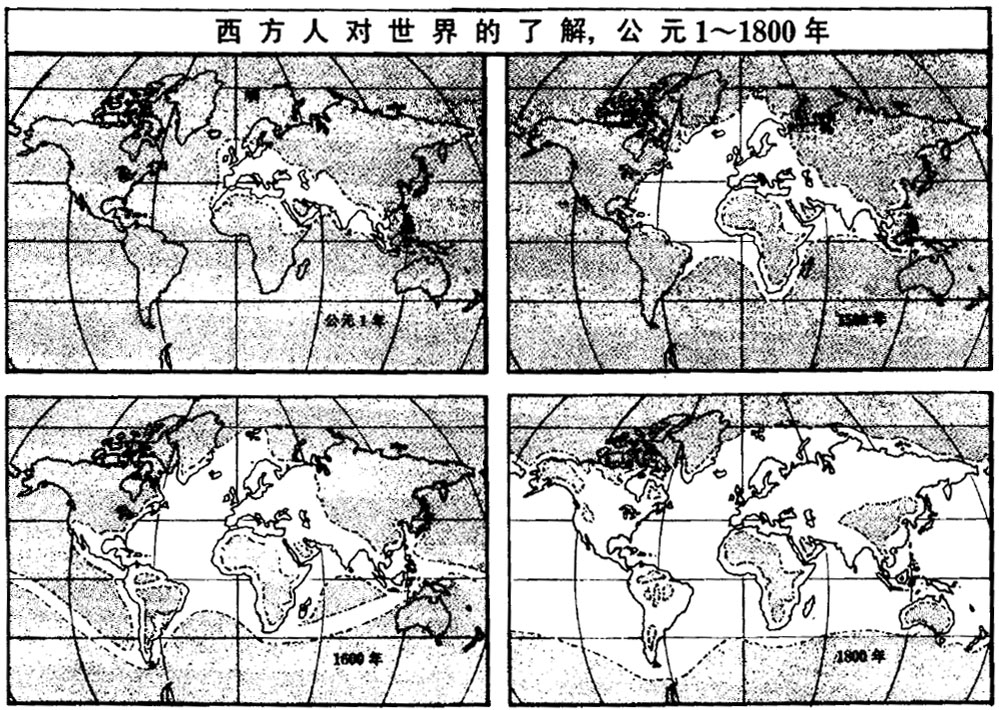

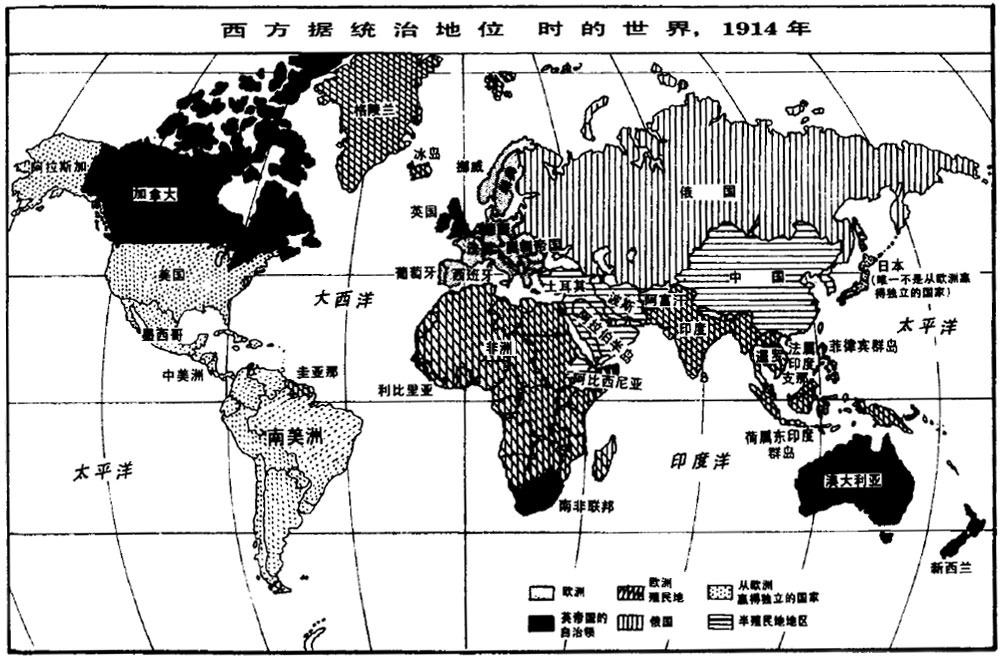

Modern world history courses often retain these traditional topics while adding other topics about historical developments in non-European regions.The net result is that the world history class is overburdened, becoming a class that is neither devoted to European history nor devoted to world history.It is therefore imperative to start afresh and build the gate on a new, truly global basis.If so, it is clear that the rise of Western Europe was a major development of world significance in the early modern period.At the end of the fifteenth century, Europe was only one, and by no means the most important, of the four centers of civilization in Eurasia.By the end of the eighteenth century, Western Europe had controlled ocean routes, organized lucrative trade across the globe, and conquered vast areas of North and South America and Siberia.Therefore, this stage occupies a prominent position in world history as a transition period from the isolation of the regions before 1492 to the establishment of world hegemony in Western Europe in the 19th century.

If the early modern period is evaluated from this point of view, it is obvious that the traditional subjects of European history are irrelevant to world history and must be discarded.Therefore, in place of and emphasis on the traditional subjects of European history courses in this book, the following three major subjects are substituted:

1.The roots of European expansion (why expansion was done in Europe and not in other Eurasian centers of civilization).

2.The Confucian, Muslim and non-Eurasian worlds on the eve of European expansion (their basic conditions, institutions and the ways in which they influenced the nature and course of European expansion).

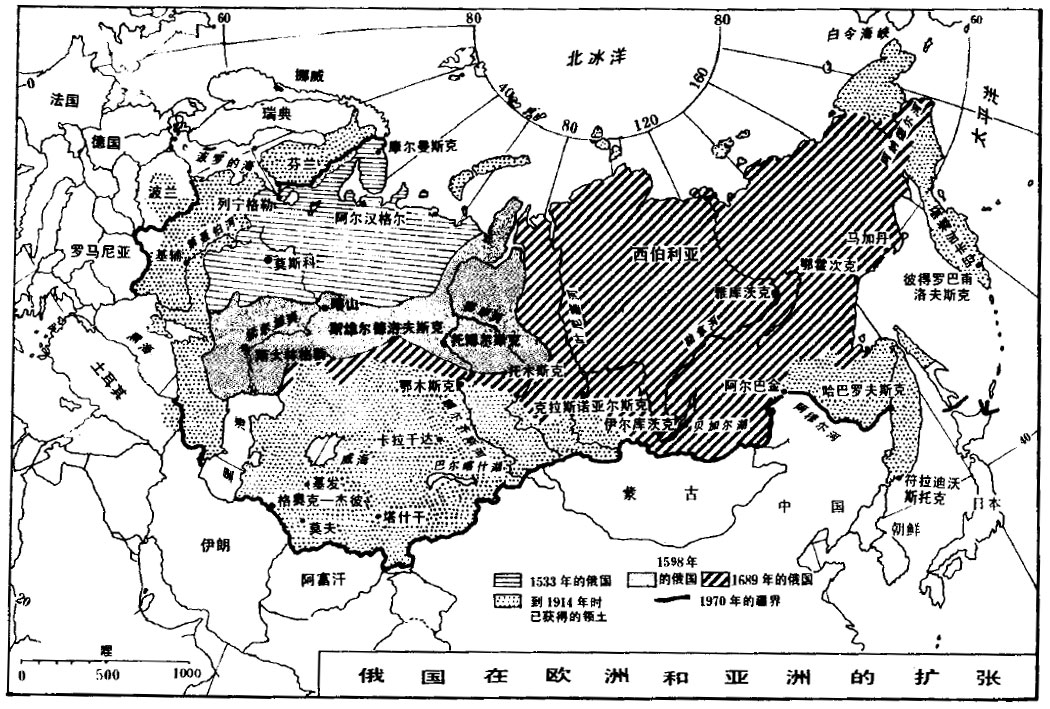

3.Phases of European expansion (Iberian phase, 1500-1600; Dutch, French, British phase, 1600-1763; Siberian-Russian phase).

This structure makes clear the main trends in world history during these centuries and, in a sense, is no more difficult to understand than the very different structure that European history classes usually follow.Furthermore, it should be noted that the role of Western Europe in the early modern period is emphasized not because the book is biased toward the West, but because, from a global perspective, Europe at this time was actually the source of world change . The same was true in the nineteenth and other centuries.In the nineteenth century, world history was dominated by European dominance; in the twentieth century, the non-Western world began to rebel against European hegemony.The fact is that since 1500 the West has been a transformative and decisive region in world affairs.Thus, in modern times, world history is centered in Europe, just as for the same reason.It was centered on the Middle East in the millennium BC, and it was centered on the Mongol Empire and the Islamic Empire in the centuries of the Middle Ages.Why is the structure of this book essentially based on Europe's rise, dominance, decline, and triumph?The reason for this is this.But, as noted above and reflected in the chapter titles of this book, being Eurocentric does not exclude a global perspective and scope.The latter two are essential to a meaningful and sustainable world history lesson.