Chapter 11 Chapter 8 The Life of the Common People

You will love these common people.

They are dirty and smelly, and they look very unpleasant, because they work day and night without distinction of cold and heat all year round, and they are described as emaciated, scarred, malnourished, and disease-ridden.Then why do you still like them?For their destinies are easy to follow; centuries after centuries they do the same thing, almost all of them farming.

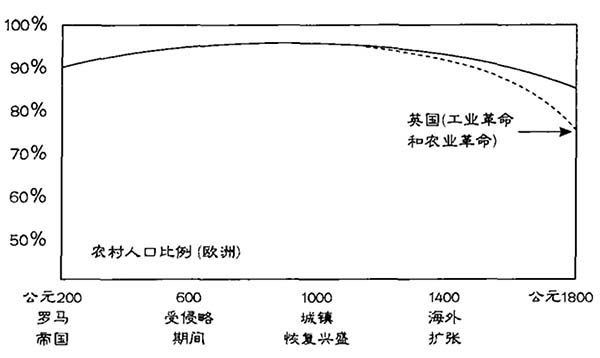

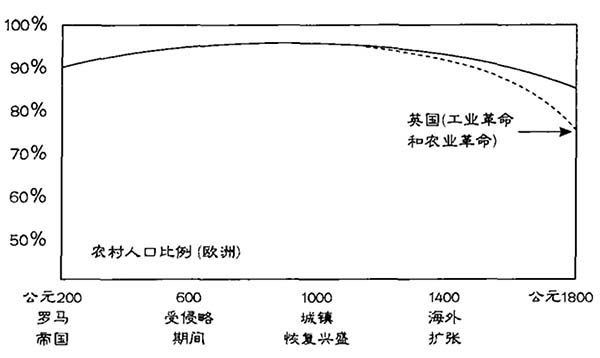

To discuss the common people, we don't need a chronology; here is a graph showing how little they changed.The graph on the next page shows the proportion of the population that cultivates food or is closely related to it, in other words, anyone who lives in a village or settlement and has an auxiliary function to agricultural production, such as a wheelwright, blacksmith or laborer, All included.These are very rough estimates.In the Roman Empire, nearly 90% of the people lived in the countryside. There were many wealthy cities in this empire, just like the predecessor of the Roman city, but the population of the cities only accounted for 10% of the whole population.

The great cities were fed by the country corn, but the corn was too heavy to be brought overland in horse-drawn carts--it would rot and lose its value.Rome's grain was shipped across the ocean from Egypt, far cheaper than other means of transportation.In the later period of the Roman Empire, in order to please the people, the government also provided subsidies for the distribution of grain in Rome; Rome at that time was like a third world city today, attracting populations flocking like a big magnet, but it could not supply the living needs of these people. need.Back then, Rome not only provided free bread, but also regularly held large-scale entertainment programs in the amphitheater.The Roman satirist Juvenal described the government’s survival by “bread and circuses.”

The grain trade was unique at the time.Most of the commercial transactions in the empire are light-weight, high-value luxury goods that can withstand long distances.Just like in Europe before the 19th century, most of the people in the Roman Empire used materials from nearby places to see what was grown or made nearby. Everything they ate, drank, wore, and lived in was locally produced.The reason why European cottages are covered with thatch is not because it is more poetic and picturesque than slate roofs, but because thatch is cheap and readily available. Therefore, economic development is not the focus of Roman innovation. The efficient military organization keeps the entire empire intact, which is their spirit of governing the country.Some of the Roman roads that intersect in straight lines still exist today. They were designed by military engineers at that time. The main purpose was to allow soldiers to move quickly from one place to another, so they are straight lines; When used with a carriage, the slope will be much gentler.

During the last two hundred years of the Roman Empire, as the Germanic barbarians invaded, cities were depopulated and trade was severely reduced, making regional self-sufficiency even more necessary.At the height of the empire, cities had no walls; Rome's enemies were kept at its borders.It wasn't until the 3rd century that the towns began to build walls along the perimeter, and the area covered by the walls later became smaller and smaller, which is more evidence of the shrinkage of the town.In 476 AD, the entire Roman Empire disappeared, and at this time the proportion of the rural population had risen to 95%.

These populations remained in the countryside for hundreds of years.After the invasion of the Germanic barbarians, other foreign races followed: the Muslims in the 7th and 8th centuries occupied southern France and invaded Italy; In the 11th and 12th centuries, peace finally came, trade gradually recovered, and urban life came back to life. After the fifth century, some towns were almost completely leveled, others were greatly reduced.

Land labor population began to decline, but very slowly. In the 15th century, Europe began to expand overseas. As a result, commerce, finance, and shipping industries rose, and cities flourished. Around 1800, the rural population of Western Europe may have fallen to 85%, slightly lower than that of the Roman Empire.Over such a long period of time, population movement has hardly changed; the only exception is the United Kingdom, whose rural population began to decline sharply around 1800 as the urban population exploded. By 1850, half of the British people lived in in the city.

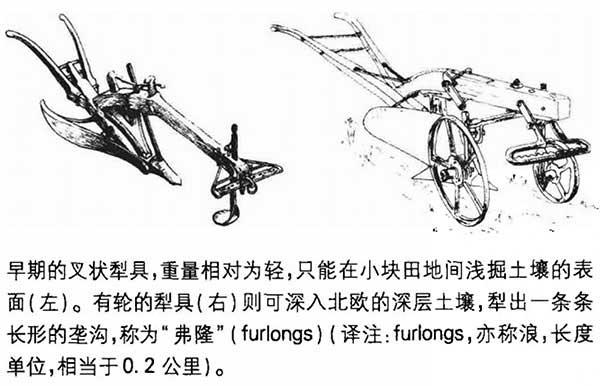

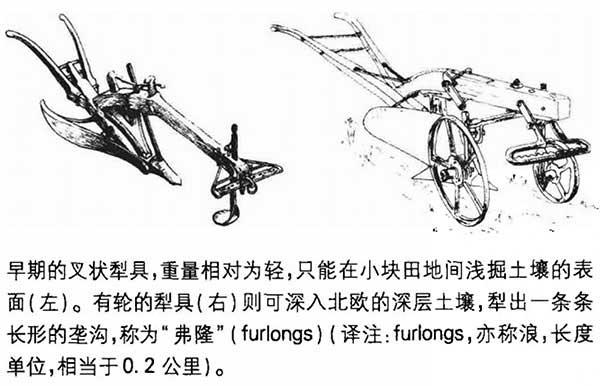

There is also a hierarchy of people who cultivate food.From time immemorial, at any age, small landowners, slaves (or freedmen ex-slaves), serfs (or freedmen ex-serfs), tenant farmers (or sharecroppers), and laborers may have been included among the cultivators. List.We commonly call them farmers.But no matter where they were or what time they were, they worked in exactly the same way; in Italy, southern France and Spain, 19th-century plowing was no different than it was in Roman times.They used a very primitive plow, you just imagine a long forked stick with a cutting blade at the bottom.An ox or a horse pulls the plow in front, and a person behind holds the plowshare to control the direction. It is difficult for the blade to go deep into the inner layer of the soil, and it can only scrape the surface shallowly.The plowing is carried out in a checkerboard manner, first going straight along the field, and then plowing down horizontally.

The great cities were fed by the country corn, but the corn was too heavy to be brought overland in horse-drawn carts--it would rot and lose its value.Rome's grain was shipped across the ocean from Egypt, far cheaper than other means of transportation.In the later period of the Roman Empire, in order to please the people, the government also provided subsidies for the distribution of grain in Rome; Rome at that time was like a third world city today, attracting populations flocking like a big magnet, but it could not supply the living needs of these people. need.Back then, Rome not only provided free bread, but also regularly held large-scale entertainment programs in the amphitheater.The Roman satirist Juvenal described the government’s survival by “bread and circuses.”

The grain trade was unique at the time.Most of the commercial transactions in the empire are light-weight, high-value luxury goods that can withstand long distances.Just like in Europe before the 19th century, most of the people in the Roman Empire used materials from nearby places to see what was grown or made nearby. Everything they ate, drank, wore, and lived in was locally produced.The reason why European cottages are covered with thatch is not because it is more poetic and picturesque than slate roofs, but because thatch is cheap and readily available. Therefore, economic development is not the focus of Roman innovation. The efficient military organization keeps the entire empire intact, which is their spirit of governing the country.Some of the Roman roads that intersect in straight lines still exist today. They were designed by military engineers at that time. The main purpose was to allow soldiers to move quickly from one place to another, so they are straight lines; When used with a carriage, the slope will be much gentler.

During the last two hundred years of the Roman Empire, as the Germanic barbarians invaded, cities were depopulated and trade was severely reduced, making regional self-sufficiency even more necessary.At the height of the empire, cities had no walls; Rome's enemies were kept at its borders.It wasn't until the 3rd century that the towns began to build walls along the perimeter, and the area covered by the walls later became smaller and smaller, which is more evidence of the shrinkage of the town.In 476 AD, the entire Roman Empire disappeared, and at this time the proportion of the rural population had risen to 95%.

These populations remained in the countryside for hundreds of years.After the invasion of the Germanic barbarians, other foreign races followed: the Muslims in the 7th and 8th centuries occupied southern France and invaded Italy; In the 11th and 12th centuries, peace finally came, trade gradually recovered, and urban life came back to life. After the fifth century, some towns were almost completely leveled, others were greatly reduced.

Land labor population began to decline, but very slowly. In the 15th century, Europe began to expand overseas. As a result, commerce, finance, and shipping industries rose, and cities flourished. Around 1800, the rural population of Western Europe may have fallen to 85%, slightly lower than that of the Roman Empire.Over such a long period of time, population movement has hardly changed; the only exception is the United Kingdom, whose rural population began to decline sharply around 1800 as the urban population exploded. By 1850, half of the British people lived in in the city.

There is also a hierarchy of people who cultivate food.From time immemorial, at any age, small landowners, slaves (or freedmen ex-slaves), serfs (or freedmen ex-serfs), tenant farmers (or sharecroppers), and laborers may have been included among the cultivators. List.We commonly call them farmers.But no matter where they were or what time they were, they worked in exactly the same way; in Italy, southern France and Spain, 19th-century plowing was no different than it was in Roman times.They used a very primitive plow, you just imagine a long forked stick with a cutting blade at the bottom.An ox or a horse pulls the plow in front, and a person behind holds the plowshare to control the direction. It is difficult for the blade to go deep into the inner layer of the soil, and it can only scrape the surface shallowly.The plowing is carried out in a checkerboard manner, first going straight along the field, and then plowing down horizontally.

The wheeled plow was one of the great inventions of the early Middle Ages, whose inventor is unknown.It is especially effective on the thick soils of northern France, Germany and England.Basically, the plow was similar to a modern tiller, only still drawn by animals and controlled by humans.In addition to having a sharp blade that digs into the soil, the plow also has a template that lifts and turns the loosened soil.This creates furrows, not just digging the surface, but the furrows are all in the same direction and parallel to each other, not parallel intersections like the old plow method.On heavy soils, irrigation water can flow down the furrow.Plowing is hard work. You don't just control the direction of the plow. If your shoulders and arms don't hold it firmly, you won't be able to dig the soil and it will overturn.After plowing the field comes sowing, which is a relatively easy task. You spread the seeds in the furrows in the field and then take a harrow—a type of rake—to cover the seeds.

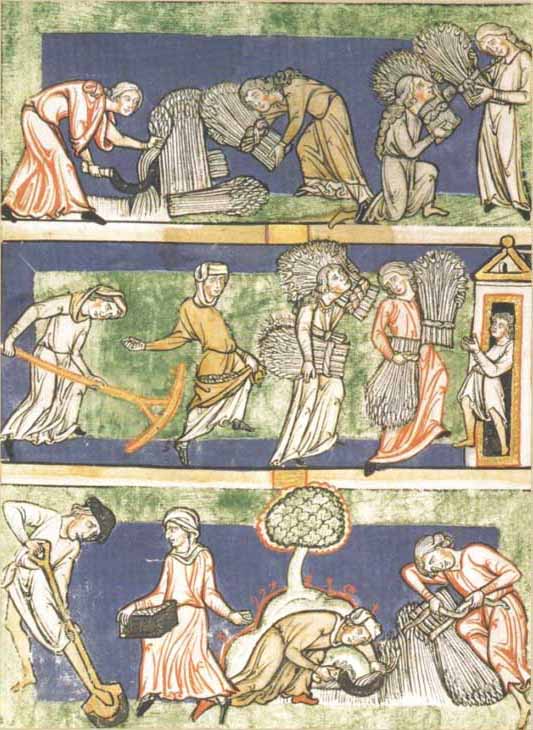

Plowing is a man's job.Harvesting involves both men, women and children, and because the safe harvest period is very short, farmers have to recruit temporary workers from towns and cities, and even local soldiers may come out of the barracks to help.The tool for harvesting was the sickle, a curved knife with a handle.Archaeologists have found sickles in some of the oldest human settlements, and until the early 20th century they remained the standard harvesting tool in Europe. In 1917, when the socialist revolution broke out in Russia, a new national flag was produced to pay tribute to the working class. The new flag had the symbols of a hammer and a sickle. The hammer meant labor in the city, and the sickle represented rural labor.

When you think of plowing and harvesting, don't think that's what you see today: farmers driving across fields in air-conditioned tractors.Year after year, inch by inch of the field is plowed by farmers toiling, hunched over, and shuffling.

The harvested barley or wheat stalks are gathered together, after which the kernels have to be threshed from the ears.The threshing implement is called a flail, which has a long handle and a flat plate attached to a strap.Spread the ears of wheat on the barn floor, then shake the handle of the flail, and the plank will move down and flatten on the ears of wheat.Keep the barn door open so that the breeze will blow the chaff away, leaving only the good grain on the ground.

These grains can be turned into flour, which is then made into bread.Bread is the backbone of life, you just eat it in big chunks, there is nothing else to choose; meat is not always available, maybe a little butter or cheese to go with the bread.Bread is the staple food, not a supporting role in a side dish, or a few slices in a pretty basket, but three or four large pieces.If you are rich, you can eat one kilogram a day, that is, one big loaf per day.Wheat is being grown everywhere, even in unsuitable areas.Because of the extreme difficulty of transportation, the grain had to be grown close to where it was consumed, and it was expensive to bring it from elsewhere.Although grain can be transported by sea, inland areas, regardless of distance, it was not possible to transport grain until the digging of canals in the 18th century.

The wheeled plow was one of the great inventions of the early Middle Ages, whose inventor is unknown.It is especially effective on the thick soils of northern France, Germany and England.Basically, the plow was similar to a modern tiller, only still drawn by animals and controlled by humans.In addition to having a sharp blade that digs into the soil, the plow also has a template that lifts and turns the loosened soil.This creates furrows, not just digging the surface, but the furrows are all in the same direction and parallel to each other, not parallel intersections like the old plow method.On heavy soils, irrigation water can flow down the furrow.Plowing is hard work. You don't just control the direction of the plow. If your shoulders and arms don't hold it firmly, you won't be able to dig the soil and it will overturn.After plowing the field comes sowing, which is a relatively easy task. You spread the seeds in the furrows in the field and then take a harrow—a type of rake—to cover the seeds.

Plowing is a man's job.Harvesting involves both men, women and children, and because the safe harvest period is very short, farmers have to recruit temporary workers from towns and cities, and even local soldiers may come out of the barracks to help.The tool for harvesting was the sickle, a curved knife with a handle.Archaeologists have found sickles in some of the oldest human settlements, and until the early 20th century they remained the standard harvesting tool in Europe. In 1917, when the socialist revolution broke out in Russia, a new national flag was produced to pay tribute to the working class. The new flag had the symbols of a hammer and a sickle. The hammer meant labor in the city, and the sickle represented rural labor.

When you think of plowing and harvesting, don't think that's what you see today: farmers driving across fields in air-conditioned tractors.Year after year, inch by inch of the field is plowed by farmers toiling, hunched over, and shuffling.

The harvested barley or wheat stalks are gathered together, after which the kernels have to be threshed from the ears.The threshing implement is called a flail, which has a long handle and a flat plate attached to a strap.Spread the ears of wheat on the barn floor, then shake the handle of the flail, and the plank will move down and flatten on the ears of wheat.Keep the barn door open so that the breeze will blow the chaff away, leaving only the good grain on the ground.

These grains can be turned into flour, which is then made into bread.Bread is the backbone of life, you just eat it in big chunks, there is nothing else to choose; meat is not always available, maybe a little butter or cheese to go with the bread.Bread is the staple food, not a supporting role in a side dish, or a few slices in a pretty basket, but three or four large pieces.If you are rich, you can eat one kilogram a day, that is, one big loaf per day.Wheat is being grown everywhere, even in unsuitable areas.Because of the extreme difficulty of transportation, the grain had to be grown close to where it was consumed, and it was expensive to bring it from elsewhere.Although grain can be transported by sea, inland areas, regardless of distance, it was not possible to transport grain until the digging of canals in the 18th century.

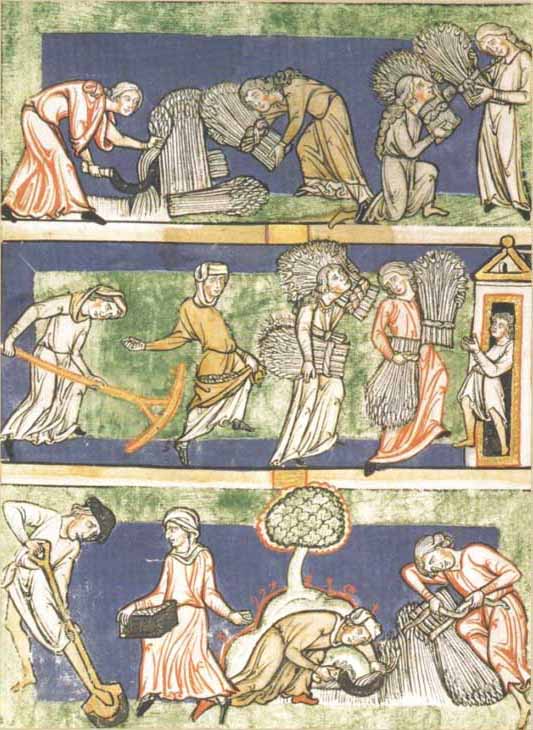

Figure 8-1 "The Model of the Virgin" (Annotation: Speculum virginum, the standard specification for the training of nuns in the 12th century), a harvest scene in a German manuscript.

All the people are always worried about the harvest.Talking about the weather is not about finding something to say, but a group of people worrying about their own fate.If the corn was premature or destroyed by bad weather before harvest, the community would suffer; they would have to bring the grain from elsewhere, and doing so would be very costly.Bread prices doubled or tripled during periods of bad grain.It's not as simple as something that's so much more expensive in the supermarket these days and you just switch to something else for a while; it means your food costs will double or triple, and if so, you'll just starve , Maybe he will starve to death.

However, food is grown by farmers, so wouldn't rising prices benefit them?This is only true for those who have large quantities of food.If you only grow enough to feed your family and have nothing left to sell, a poor harvest means you can't even feed yourself and have to buy it outside.Some people's fields are small, even if the harvest is not enough for the family, these people have to do odd jobs for the big landlords in order to buy more food.Many laborers do not have their own fields at all. If they live with their employers and the employer takes care of food and housing, that is not bad. But if they live in their own thatched huts, they have to buy bread frequently.Of course, those who live in the cities will always have to buy their bread, so if the price of grain goes up, many will be in dire straits.

Once there is a shortage of grain, the owners of grain—the people who grow it in large numbers and trade it in—are likely to stockpile it and wait for the price to continue to rise, or to sell it elsewhere where the price has risen more fiercely, and so on. Come, the locals will have no food to eat.After about 1400, European governments gradually became stronger and tried to control the grain trade.They have decrees prohibiting hoarding, and merchants are not allowed to transport food that is already in short supply locally. If local officials do not enforce these decrees, the people are likely to implement them themselves.They scoured everywhere to stockpile grain, forced the big farmers to take out grain to sell, and even attacked the wagons or ships that transported grain to other places.Because of the threat of riots and social disorder, the government has no choice but to intervene.

Most people live with uncertainty about food most of the time.It is a luxury to be able to eat a good meal; obesity is beauty; holidays are days of feasting.The way we celebrate Christmas in the modern world is still a sad legacy of this phenomenon, in other words, we look forward to marking the day with food and drink, even though we eat well enough on weekdays.I'm also trying to preserve a bit of the original spirit of the holiday right now—no turkey on other days.

It is these land laborers who account for 85 to 95 percent of the total population that create civilization.No city or lord, priest or king, or even an army could exist if the peasant grew only enough food to feed himself—these people all depended on others to grow what they fed.Whether farmers like it or not, they have to feed others.This phenomenon was most prominent in the serfs in the early Middle Ages. They had to submit part of their crops to the lord as rent, some to the church as donations, and they had to work unpaid in the lord's fields so that the lord himself could have a harvest.In the end, the obligation to work for the lord ceased, and it was only necessary to pay the lord and the priest.

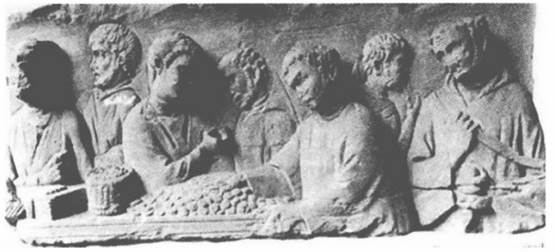

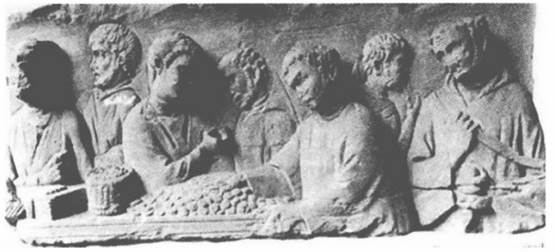

In the early Middle Ages, the state did not levy taxes; before the Roman Empire and later in the emerging European countries, farmers had to pay taxes.There is a relief here showing how the Roman Empire collected taxes, depicting tax collectors and peasants who came to pay taxes.These transactions, written not on paper but on waxed boards, were the most crucial transactions that kept the empire going: the king took money from the peasants and used the money to pay the salaries of the soldiers.

Squeezing money out of peasants is the cornerstone of civilization.You can see how clean the tax collection process is.You don't have to write a check or send a check to the tax collector. He doesn't take a deduction from the money you earn. The tax collector is a real person and can find you anywhere in the world; Weapons come back and force you to pay.The matter of paying taxes is not handled by a bureaucracy, but a face-to-face confrontation.In the Roman Empire, these tax collectors were called "publicani," that is, people who collected taxes from the people.Everyone hates them, they are the worst people in the world, even Jesus helped to shape this stereotype;

Figure 8-2 During the Roman Empire, a scene of farmers paying taxes to tax collectors (note the account book on the left).This relief sculpture found in the area of the Rhine River was created around 200 AD.

He says it's no great virtue to love those who love you - even tax collectors do it.In the King James Version of the Bible, "publicani" is translated into English as "publicans".Jesus was criticized for conflating "tax collectors with sinners," which was unfair to licensed public officials.

Of course, to say that farmers are being squeezed is a very emotional term.Maybe they should be happy to pay taxes, or at least complain; no one likes to pay taxes, but it's good for everyone, to get the services the government provides.The problem is, farmers weren't served at all back then.The government runs neither schools nor health care; most governments don't even care about roads—because roads are a local affair unless they are of military importance.The Roman government took care of the sanitation of the cities, providing water and drainage systems, but did not care about the countryside.Eighty to ninety percent of the government's tax revenue is spent on the military.So, keeping out foreign aggression should be good for farmers, right?not necessarily.For the farmer, war meant that his land would be at war, and his food and animals would be used to feed armies on both sides.

In addition to being threatened by force, those who were higher than the peasants also insisted that the peasants were inferior and had to obey. The peasants had no choice but to continue to pay taxes, but protests, riots and rebellions still occurred from time to time.The peasants thought that if the king, the bishop, and the landowners all left us alone, we would be fine too.It is easy for them to have such an idea, because farmers grow their own crops, build their own houses, make their own wine, and weave their own cloth to make clothes.

Many modern people also choose to withdraw from the life of the camp.They think that they only need a piece of land, and they can grow and eat to survive.It doesn't take long for them to discover that they need money to buy jeans, medicine, alcohol and videotapes, as well as gas and phone bills.Before long, these back-to-basics folks started working part-time and slowly abandoned their farms; before long, they were back working 9-5.However, for farmers at the time, they were really self-sufficient.In their view, the government and the church are nothing but burdens, and asking for money is no different than robbery.

Peasant uprisings were always suppressed—until the early years of the French Revolution, French peasants, like peasants elsewhere, were of medieval serf origin.At the end of the Middle Ages, the serfdom system in Western Europe came to an end, and each country had different ways of dealing with these serfs who had recovered their freedom.In France, the law stipulates that the peasant is the owner of the field and can sell the land and move it elsewhere.However, whether it is these people or those who bought their land, they still have to pay fees to the old feudal lords, and they still have obligations to the lords. For example, when the lord’s daughter gets married, they have to give gifts, or A few days a week they had to work voluntarily in the lord's fields.Later, these gifts and services were changed to be paid by money. Therefore, these peasants who own the land still have to pay a bunch of miscellaneous rents. They are both landlords and tenant farmers, which is an extremely rare situation.

And the person who owns a large field may be a lord, and now he is also a wealthy middle class. They will hire some smart lawyers to investigate and see if the farmers have paid all the due fees and obligations with the money.Inflation was not taken into account when these fees and obligations were converted into money. In modern terms, these payments did not reflect the inflation index. omissions or miscalculations.Nothing is more irritating than a relationship in which a lord sees a field transferred to a farmer and, to make up for the loss, uses the old fees as an excuse to demand more money.The peasants decided to start fighting back, rallied together, hired lawyers themselves, and declared war on their lords.

In 1788, the king of France held a three-level meeting. The peasants thought that the dawn of a change of sky would finally relieve all their hated robbery. However, things have not progressed, which is suspicious; The National Assembly is recognized, but they still have to pay the lords, there must be a conspiracy; the price of bread is getting more expensive every day, because the previous harvest is very poor, and the new harvest is not yet in season.Rumors abounded in the countryside that nobles and bullies were doing everything they could to thwart reforms in the countryside.The peasants really got up and took action, ran to find those bullies to settle accounts, and beat them to death.They also went to the lord's castle, demanding that the lord or his agent destroy the large account book that registered the payment. If the lord nodded, they would disperse contentedly, and if the lord refused to nod, they would burn the castle.

Peasant rebellion spread across the countryside, and the revolutionary party in Paris did not know what to do, which was completely unexpected.If the time is right, once they have a Bill of Rights and a new constitution, they will seek to resolve the farmers' grievances.The problem is that there is no shortage of people among these revolutionary parties who use this to collect money from the peasants.

Whenever the peasants rebelled, the king's response was usually to send troops to suppress it, but the revolutionaries did not want this; if the king ordered the army to be sent, it was likely that the army would be used to deal with the revolutionaries after the peasants' rebellion was resolved.The leaders of the council decided to follow the will of the people and give the peasants what they wanted. On August 4th, 1789, Parliament met all night and announced the abolition of all field fees and obligations.Those who profited from it in the past blamed each other and promised reform, but it was half staged show, half hysteria.The government, however, was not completely carried away. They wanted to draw a line where payments for private services would be abolished immediately, but fees related to real estate would be lifted later, and some compensation would be given to the landowners.But this division is very difficult to determine. The farmers refused to draw the line and insisted that they would not have to pay any money from now on. In 1793, as the methods of the revolution became more violent, and a new constitution was drawn up, all fees and obligations were abolished.

Today, French peasants have become true landowners, no longer tied to any landowners. They later became a conservative force in 19th-century French politics, fighting with the city's attack on private property and eager to create communism. The radical working class of society is divided against each other.In France, the big bosses can always rely on these peasants to vote down such communist proposals.Farmers cling to small fields, and French agriculture will always be an inefficient small-scale operation.Today, those farmers benefit from European subsidies, which means they can sell their crops cheaper to compete with Australia's more efficient and larger farmers.Now the French peasants are squeezing us!

As for England, after the end of serfdom, the arrangement of land was very different.Feudal fees and obligations of any kind are gone.Serfs became tenant farmers according to the modern method, that is, they simply paid rent to the landlord.

The tenants signed leases, sometimes for very long periods, or even for life, but once the lease expired, the landlord could replace the tenant and lease the land to someone else.In France, the peasants have greater security, and the landlord cannot replace the peasant, but the peasant must pay feudal fees and obligations; in Britain, there is a modern commercial relationship between the landlord and the tenant, which has contributed to its great leap forward in agricultural productivity, called agriculture revolution.

This revolution has two major elements: advances in farming methods and a reorganization of land tenure.It had nothing to do with improvements in farm machinery; tractors and harvesters were much later.

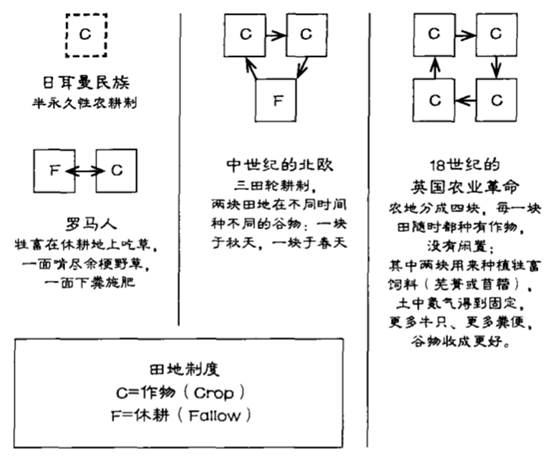

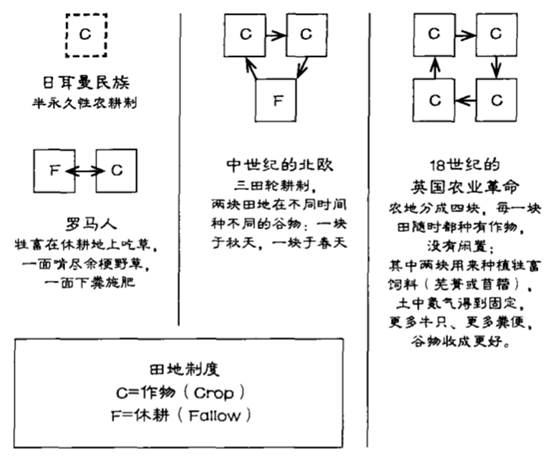

Let me talk about farming methods first.Frequent tillage can deplete the soil of nutrients, a fundamental dilemma faced by all cultivators.How to solve it?If it is a Germanic nation outside the Roman Empire, farmers will directly relocate to a new piece of land to cultivate after the old land is exhausted. This can only be regarded as semi-permanent agriculture.

As for the territory of the Roman Empire, the farm land will be divided into two halves, one half is planted with crops, and the other half is fallow, which means that nothing is planted to let the field rest. The manure can also be used as fertilizer.At the end of the year, the farmer turns over the fallow land to transplant seedlings and plant new crops, and it is the turn of the other half to start fallow. This was the practice in southern Europe until the 19th century.

In northern Europe in the Middle Ages, the three-field rotation system was developed, in which two fields were planted, one was planted in autumn, the other was dug and sown in spring, and the third was left fallow.Clearly, this was a considerable efficiency gain: at all times, two-thirds of the field was producing grain instead of one-half.

In England in the 18th century, the agricultural land was divided into four parts, each of which was planted with crops. This was the Agricultural Revolution.Why is it so effective?If a piece of land has been planted with grains, the nutrients will be depleted.The clever thing about this approach is that two of the fields grow grain as usual, while the other two grow livestock feed, such as turnips or alfalfa.These crops draw nutrients differently from the soil, so the soil doesn't become depleted from growing grains.In fact, alfalfa can also fix atmospheric nitrogen in the soil and increase its nutrients.As farmers also began to grow animal feed crops, enough to feed more cattle and sheep, instead of leaving the animals to fend for themselves on fallow land as in the past; because the animals were well fed, they not only grew fatter, but also produced more manure.At the end of the year, when the cattle and sheep fields are turned to planting grains, the growing crops will have a better harvest.The more livestock are raised, the better they are raised, and the harvest of crops is also increasing. This is the result of the new four-field farming method.

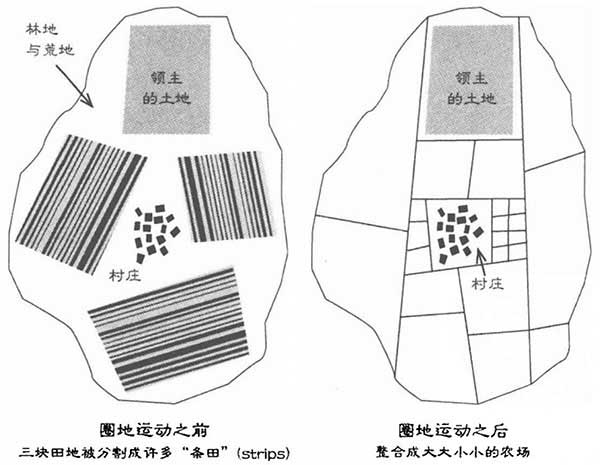

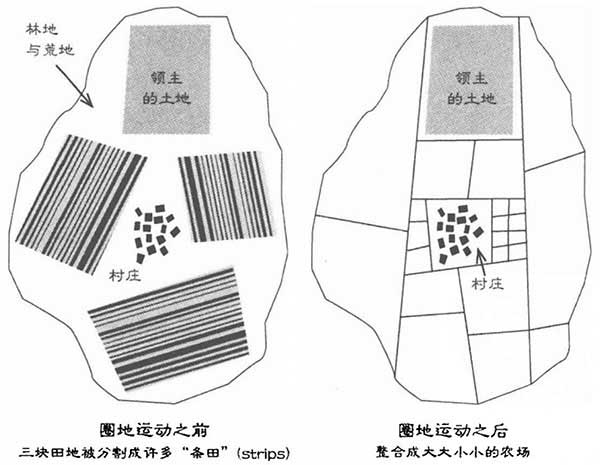

At the same time, the land is also re-planned. Every farmer has a stable land right and clear boundaries. This kind of planning has replaced the past agricultural land system. The land is subdivided into many long strips (called strip fields), and each farmer cultivates only one strip field.You don't have your own farm, the farm belongs to the whole village, and the ownership of the farm is in the hands of the lord.It was up to the village to decide what, when, and where the fields were to be planted; everyone's cattle grazed on the fallow land.Except for these three public cultivated lands, the others are wastelands, swamps or woodlands, which are not only open to livestock grazing for all, but also for people to cut thatch or collect firewood.

It is the benevolent policy of the Congress to reorganize agricultural land into clear land rights, especially for the situation of each village.The British Parliament was a collection of great landowners who believed that fixed enclosures (or enclosures, as they were known) were necessary for the new farming laws to be effectively implemented.Planting new crops and caring for livestock all require individual attention, not the collective control of the entire village.Landlords who want to increase the yield of their land and increase the rent they charge can add a condition to the lease: those who rent the rezoned land must adopt new farming methods, and farmers who refuse to grow turnips will be eliminated, in other words , the lease will not be renewed upon expiration.

The rezoning was carried out with great care.The responsible official first carefully surveys all the villagers to determine what rights they currently have, and then converts each person's right to work on the public land and the right to graze on the public land to a certain large or small rezoning land. ownership.The most disadvantaged are those villagers who could only graze on the public land before. They can only get a small amount of land, and there is no benefit at all.These are the people who are most likely to leave the country for a living in the city.However, on the whole, the labor required for farming in new ways on newly planned land has not decreased but increased.The rural population does have a tendency to flow to the city, but this is due to rapid population growth.

At the same time, the land is also re-planned. Every farmer has a stable land right and clear boundaries. This kind of planning has replaced the past agricultural land system. The land is subdivided into many long strips (called strip fields), and each farmer cultivates only one strip field.You don't have your own farm, the farm belongs to the whole village, and the ownership of the farm is in the hands of the lord.It was up to the village to decide what, when, and where the fields were to be planted; everyone's cattle grazed on the fallow land.Except for these three public cultivated lands, the others are wastelands, swamps or woodlands, which are not only open to livestock grazing for all, but also for people to cut thatch or collect firewood.

It is the benevolent policy of the Congress to reorganize agricultural land into clear land rights, especially for the situation of each village.The British Parliament was a collection of great landowners who believed that fixed enclosures (or enclosures, as they were known) were necessary for the new farming laws to be effectively implemented.Planting new crops and caring for livestock all require individual attention, not the collective control of the entire village.Landlords who want to increase the yield of their land and increase the rent they charge can add a condition to the lease: those who rent the rezoned land must adopt new farming methods, and farmers who refuse to grow turnips will be eliminated, in other words , the lease will not be renewed upon expiration.

The rezoning was carried out with great care.The responsible official first carefully surveys all the villagers to determine what rights they currently have, and then converts each person's right to work on the public land and the right to graze on the public land to a certain large or small rezoning land. ownership.The most disadvantaged are those villagers who could only graze on the public land before. They can only get a small amount of land, and there is no benefit at all.These are the people who are most likely to leave the country for a living in the city.However, on the whole, the labor required for farming in new ways on newly planned land has not decreased but increased.The rural population does have a tendency to flow to the city, but this is due to rapid population growth.

Agricultural productivity increased and urban growth became possible.Overall, fewer people can now feed everyone.Britain was the first major modern country in the world to make such a major leap forward.Some agricultural improvers in France thought of others and wanted to do similar land rezoning. However, the land in France is owned by farmers, and the concept of co-governance is deeply rooted, and even the autocratic monarch can't do anything.

After the mid-18th century, the British Industrial Revolution and Agricultural Revolution began to connect and complement each other.Cotton and wool are no longer handed over to the workers in the village for spinning and weaving. This task is transferred to the factory for it.These factories housed the latest inventions, first powered by waterwheels and then by steam engines.The laborer becomes the caretaker and maintainer of the machine, commuting to and from get off work on time, working for the boss rather than being his own master.Towns with cotton and wool mills grew in population; thanks first to a network of canals and waterways, then a network of railroads, all new economic activity was linked.Finally, there is a country that can cheaply ship bulk goods to every other corner.

The British Industrial Revolution was not a product of planning.It was brought about by the careful planning, promotion and protection of industry by the despotic governments of the European countries, where the government was controlled by Parliament, in order to increase the economic and military power of the country.The British aristocracy and landed gentry, that is, members of Parliament, had a stronger incentive to speed up because of their involvement in new economic activities.The old rules governing industry and employment were swept aside and rendered useless.

The social changes triggered by these two revolutions were painful.Yet the world's first industrial-cum-metropolitan state offered the vision that it would lead to a level of unimaginable affluence for what used to be just enough to survive, the hard-working commoners.

Agricultural productivity increased and urban growth became possible.Overall, fewer people can now feed everyone.Britain was the first major modern country in the world to make such a major leap forward.Some agricultural improvers in France thought of others and wanted to do similar land rezoning. However, the land in France is owned by farmers, and the concept of co-governance is deeply rooted, and even the autocratic monarch can't do anything.

After the mid-18th century, the British Industrial Revolution and Agricultural Revolution began to connect and complement each other.Cotton and wool are no longer handed over to the workers in the village for spinning and weaving. This task is transferred to the factory for it.These factories housed the latest inventions, first powered by waterwheels and then by steam engines.The laborer becomes the caretaker and maintainer of the machine, commuting to and from get off work on time, working for the boss rather than being his own master.Towns with cotton and wool mills grew in population; thanks first to a network of canals and waterways, then a network of railroads, all new economic activity was linked.Finally, there is a country that can cheaply ship bulk goods to every other corner.

The British Industrial Revolution was not a product of planning.It was brought about by the careful planning, promotion and protection of industry by the despotic governments of the European countries, where the government was controlled by Parliament, in order to increase the economic and military power of the country.The British aristocracy and landed gentry, that is, members of Parliament, had a stronger incentive to speed up because of their involvement in new economic activities.The old rules governing industry and employment were swept aside and rendered useless.

The social changes triggered by these two revolutions were painful.Yet the world's first industrial-cum-metropolitan state offered the vision that it would lead to a level of unimaginable affluence for what used to be just enough to survive, the hard-working commoners.

Figure 8-1 "The Model of the Virgin" (Annotation: Speculum virginum, the standard specification for the training of nuns in the 12th century), a harvest scene in a German manuscript.

Figure 8-2 During the Roman Empire, a scene of farmers paying taxes to tax collectors (note the account book on the left).This relief sculpture found in the area of the Rhine River was created around 200 AD.